Whatever one’s personal background and aspirations may be, Carnatic music bamains a quest for undiluted aesthetic experience (rasa).1 Three basic concepts are essential for daily practice as well as proper appreciation: rāga (tuneful rendition with minute intervals and rich in embellishments), tāla (rhythmic order marked by mathematical precision), and bhāva (expression of thoughts and emotions).

To appreciate how these qualities are being inculcated, listen to the very first song taught for generations and from a very young age – long before a learner grasps the other concepts that distinguish “classical” Carnatic music from its popular counterparts (devotional, folk and film music):

contributed by Sreevidhya Chandramouli | Lyrics, notation and translations >>

The origins of South Indian music are traced to prehistoric times. Musical instruments form a favorite subject for sculptors, painters and the authors of ancient Tamil and Sanskrit texts. Vocal and instrumental genres have have since coalesced into a single body of compositions and themes. These form the basis for creative elaboration and self-expression.

Several strands have been intertwining throughout Indian music history. The celebrated Kannada writer and dramatist, Kota Shivarama Karanth, went so far as to declare that Indian culture today is so varied as to be called ‘cultures’.2

Music was cultivated by nobility and common people alike. A mere glance at India’s literary heritage, including poetry, drama, mythology and scholarly texts, reveals an ongoing quest for new ideas. The same can be said of performers, instrument makers and skilled amateurs. The resulting “art music” is in fact an amalgam of different “regional” or “indigenous” styles (dēsi). Today it is being studied all over the world on account of its continuity, infinite variety and a rare capacity for self-rejuvenation.3

Carnatic music owes its name to the Sanskrit term Karnātaka Sangītam which denotes “traditional” or “codified” music. The corresponding Tamil concept is known as Tamil Isai. These terms are used by scholars upholding the “classical” credentials and establish the “scientific” moorings of traditional music. Besides Sanskrit and Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam have long been used for song lyrics.

Tips for using the interactive Carnaticstudent-map >>

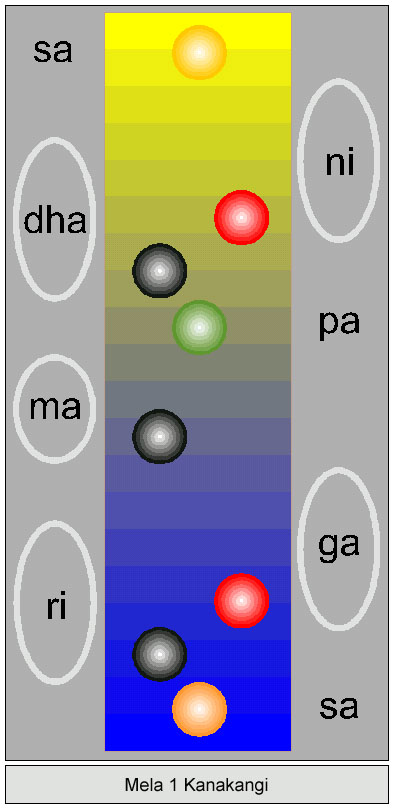

Purandara Dāsa (1484-1564),4 the prolific poet-composer and mystic of Vijayanagar, introduced a music course that is followed to the present day. Since the 17th century, hundreds of rāga-s (melody types) have been distributed among the 72 melakarta rāgas (scales).

The type of song prevailing today, known as kriti (lit. “creation“), was popularized by the most revered poet-composer of South India, Tyāgarāja (1767-1847), his contemporaries Syāma Sāstri and Muttusvāmi Dīkshitar (together known as the “Trinity” of Carnatic music), and their disciples.

Entaro mahanubhavulu

“To as many great souls as there be I bow respectfully”5

rendered by K. Sai Shankar (vocal & tambura, Kalakshetra, private recording, 1:19) | Rendition with accompaniment by Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar (GoogleDrive, 0:15) | Lyrics search >>

at Kalakshetra

Photo © Ludwig Pesch

Their songs built on the kīrtana tradition – lilting, easy to remember tunes suited for the congregational singing of South and North Indian lyrics just as those of Bengal.6

Comprising two or three melodic themes (pallavi, anupallavi and charanam), these songs continue to kindle creativity, even displays of virtuosity, among today’s singers and instrumentalists.

The modern-day kutcheri concert format emerged as late as the 20th century and is still widely followed today, in spite of much debated challenges by contemporary musicians like T.M. Krishna who seeks to “remove the barriers imposed by the music” through both, his concerts and in writing.7

A performer may draw inspiration from sacred texts8 and epics, mythology, aphorisms, patriotic poetry, stories, customs such as festivals, and dances associated with a particular place of pilgrimage or centre of learning; and conclude with “light” songs such as lullabies and love poetry (tukkada items).9

Mangalamapalli Balamuralikrishna – one of the most revered singer-composers of Carnatic music of all times – reminded his students and listeners time and again that tradition without innovation has no meaning. “His daring efforts to tread unchartered territories in music and to look at music as a whole being larger than the mere sum of parts are also his strengths.” (The Hindu, 30 July 2015)

Text: Ludwig Pesch >>

Tips: this website offers many resources free of cost and ad-free while respecting the rights of their creators (see menu for details). To learn more about the above mentioned composers and scholars, visit the places where they flourished just as the musicians who tread in their footsteps today.

Enjoy your exploration of a wonderful music!

Learn more about the tambura (tanpura) >>

Tambura posture, fingering & therapeutic effect

By Rama Kausalya

The Tambura is considered queen among the Sruti vadhyas such as Ektar, Dotar, Tuntina, Ottu and Donai. Although tamburas are traditionally made at several places, the Thanjavur Tambura has a special charm.

Veena Asaris are the Tambura makers too but not all are experts, the reason being it requires a special skill to make the convex ‘Meppalagai’ or the plate covering the ‘Kudam’ (Paanai).

There are two ways of holding a Tambura. One is the “Urdhva” – upright posture, as in concerts. Placing the Tambura on the right thigh is the general practice. The other is to place it on the floor in front of the person who is strumming it. While practising or singing casually, it can be placed horizontally on the lap.

The middle finger and index finger are used to strum the Tambura. Of the four strings, the ‘Panchamam’, which is at the farther end is plucked by the middle finger followed by the successive plucking of ‘Sārani’, ‘Anusārani’ and ‘Mandara’ strings one after the other by the index finger. This exercise is repeated in a loop resulting in the reverberating sruti.

Sit in a quiet place with eyes closed and listen to the sa-pa-sa notes of a perfectly tuned Tambura – the effect is therapeutic.

Except a few, the current generation prefers electronic sruti accompaniment, portability being the obvious reason. Besides few music students are taught to tune and play the tambura. Beyond all this what seems to swing the vote is that the electronic sruti equipment with its heavy tonal quality can cover up when the sruti goes astray.

During the middle of the last century, Miraj Tambura (next only to the vintage Thanjavur) was a rage among music students, who were captivated by its tonal quality with high precision and the beautiful, natural gourd resonators.

Source: “Therapeutic effect”, The Hindu (Friday Review), 30 March 2018

Learn & practice more

A brief introduction to Carnatic music (with music examples and interactive map)

Bhava and Rasa explained by V. Premalatha

Free “flow” exercises on this website

Introduction (values in the light of modernity)

Video | Keeping tala with hand gestures: Adi (8 beats) & Misra chapu (7 beats)

Why Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever

Worldcat.org book and journal search (including Open Access)

- “Bharata mentions eight dominant emotional moods, or sthāyibāva-s, that may be aroused by a dramatic representation into the state of aesthetic pleasure. These are rati (love), hāsa (laughter), śōka (sorrow), krōdha (anger), utsāha (energy), bhaya (fear), jugupsā (repugnance) and vismaya (wonder); the rasa-s corresponding to these are respectively called śṛṅgāra, hāsya, karuṇa, raudra, vīra, bhayānaka, bībatsa and adbhuta. Later writers accept a nineth rasa called śānta corresponding to the sthāyibāva of nirvēda (detachment).” – Dr. V. Premalatha | Learn more >> [↩]

- Quoted by historian Ramachandra Guha in “Melody within” – Politics and Play: India’s classical music may be the best antidote to chauvinism” (The Telegraph, 6 June 2020) [↩]

- For details, see Unity in Diversity, Antiquity in Contemporary Practice? South Indian Music Reconsidered (Goettingen University Press, Open Access), an essay by Ludwig Pesch [↩]

- A highly readable overview of various social and historical factors that distinguish Carnatic music is provided in the chapter titled “Songs from the soul: 1805–1847” in Modern South India: A History from the 17th Century to our Times by Rajmohan Gandhi, pp. 151-3 [↩]

- For clear translations of this composer’s lyrics, see Tyagaraja: Life and Lyrics by William J. Jackson, OUP Madras 1991 (for Entaro mahanubhavulu, see p. 210) [↩]

- According to Reba Som, Rabindranath Tagore (who didn’t know how to write music) “was often attracted by the distinctive styles of regional music [and] wrote about the great evocative power of tunes wafting across distances–carrying the message of an unknown address whispered in the ear by a traveller–bringing a note of hope and encouragement across oceans of divide.” Among these regional styles was Carnatic music with which he became acquainted “during his stay with civil servant brother Satyendranath in Karwar in western India”, an interest sustained during his 1919 visit to Madras where “he had heard with pleasure instrumental recitals on the veena in the south Indian style”.

Reba Som, Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song, New Delhi: Penguin 2009 [↩] - This is, for instance, evident in a review of his book, A Southern music, by Deepa Ganesh: “It is not easy to be T.M. Krishna. He will raise questions, challenge existing notions, unmindful of what the consequences will be” (The Hindu, 20 March 2014) [↩]

- “Musicians and listeners must have been aware long before the abstract conception of scales came into use that different tone collections tend to elicit different emotions. […] The reason for this liturgical restriction [in the context of Western music] was presumably to maintain a mood of subdued reverence that differed from popular (‘folk’) music that then, as now, elicits more carnal emotions pertinent to the needs, desires, and disappointments of daily life.” – Dale Purves in “Major and Minor Scales”, Music as Biology: The Tones We like and Why (Harvard University Press 2017), pp. 79-80 [↩]

- “Outside drama, there were other situations when rāga was associated with kāla. These were the temple rituals and social functions. In a temple, the Āgamic texts prescribe rituals which had to be performed during different parts of the day. Invariably with every ritual, there was performance of music, in the form of singing or playing the Nāgasvara and for each part of the day, a particular rāga or some rāga-s were prescribed. In social functions like marriages too, specific rāga-s are prescribed to be played on the nāgasvara during early morning and other times of the day.” – V. Premalatha (Central University of Tamil Nadu, Thiruvarur) in “Association of Rasa and Kāla (time) with Rāga-s” [↩]