Download this audio file (2 MB, 2 min. mono)

Credit: eSWAR / FS-3C Sruthi petti + Tanjore Tambura

Sikkil Mala Chandrasekhar rendering

Bhogindra Sayinam (Kuntalavarali, Khanda capu) by Svati Tirunal

Excerpt © HMV Marga 1996 cassette recording

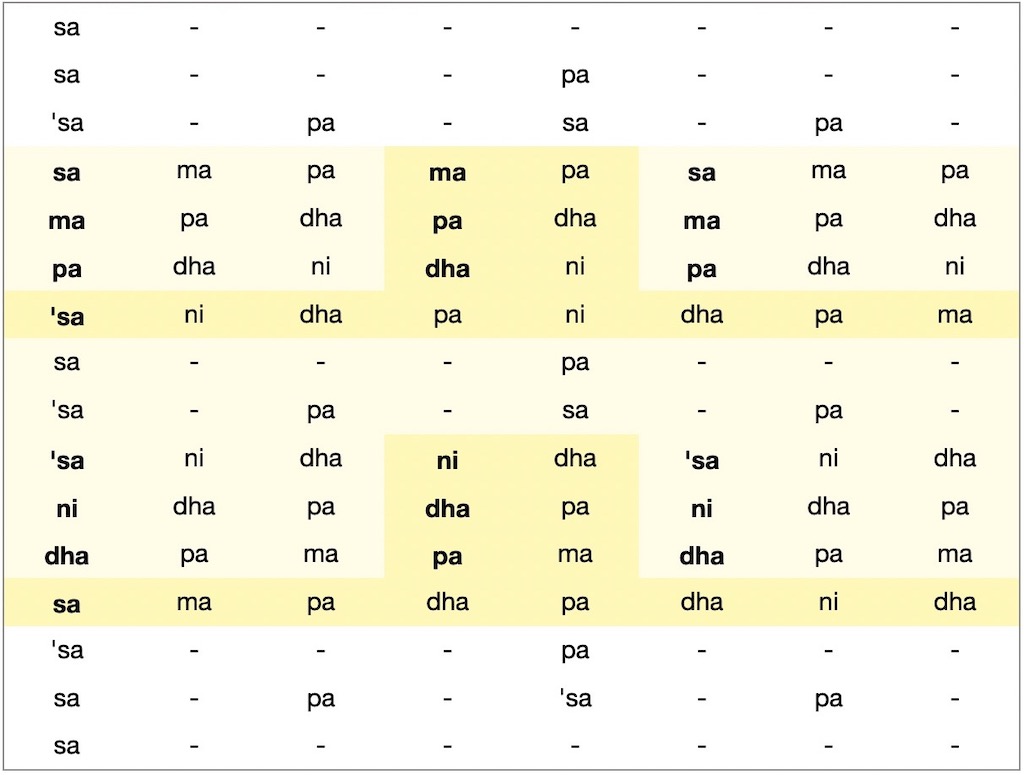

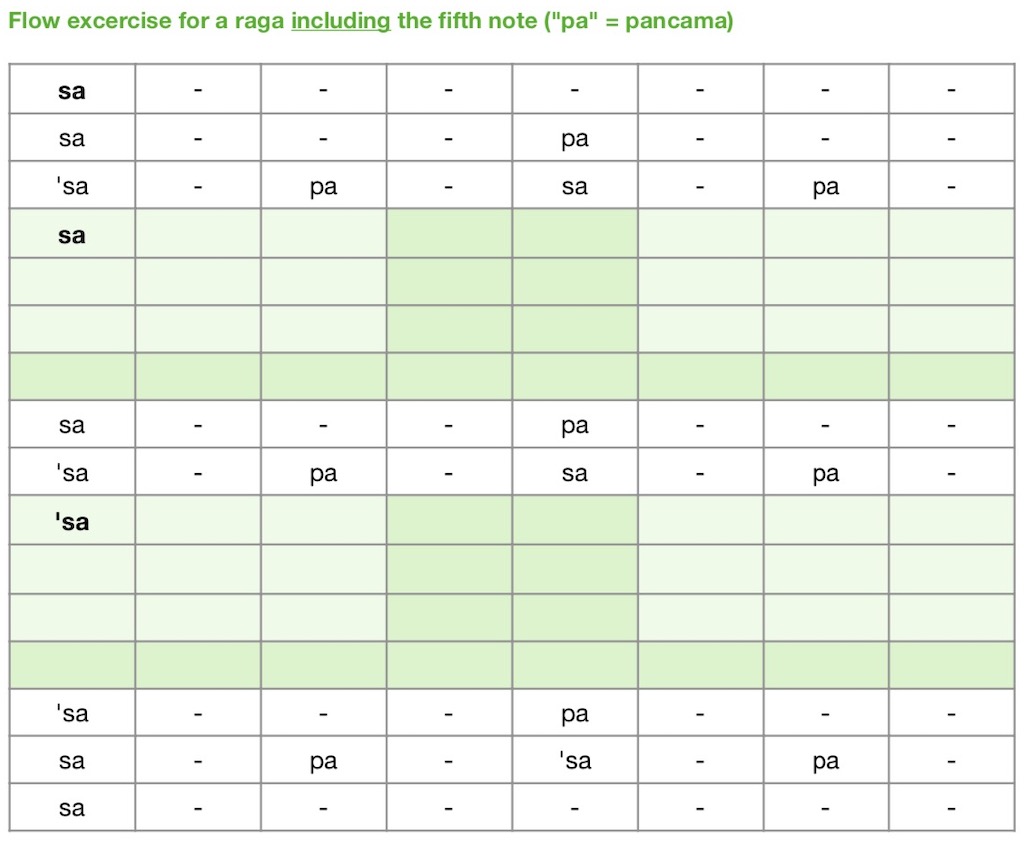

“Flow” exercises

A series of “Flow” exercises invites learners to practice all the 72 musical scales of Carnatic music (“mela” or mēlakarta rāga). It is meant to supplement the comprehensive standard syllabus (abhyāsa gānam) attributed to 16th c. composer Purandara Dasa.

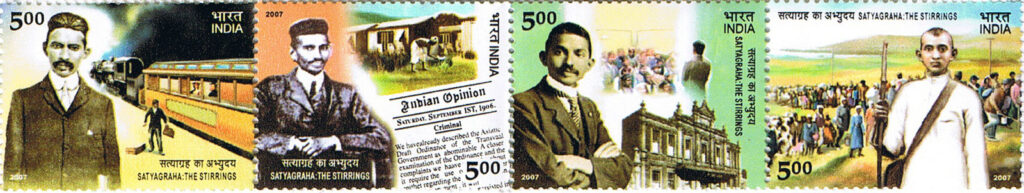

Repeated practice need not be tedious; instead it instantly turns joyful whenever we remind ourselves that Indian music “is created only when life is attuned to a single tune and a single time beat. Music is born only where the strings of the heart are not out of tune.” – Mahatma Gandhi on his love for music >>

As regards “time beat” in Carnatic music, the key concept is known as kāla pramānam: the right tempo which, once chosen, remains even (until the piece is concluded). | Learn more >>

Music teachers will find it easy to create their own versions: exercises that make such practice more enjoyable. | Janta variations >>

Concept & images © Ludwig Pesch | Feel free to share in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license >>

Become fluent with the help of svara syllables (solmisation): practice a series of exercises, each based on a set of melodic figures that lend themselves to frequent repetition (“getting into flow”) | Practice goal, choosing your vocal range & more tips >>

South Indian conventions (raga names & svara notation): karnATik.com | Guide >>

raagam: kuntalavarALi

Aa: S M1 P D2 N2 D2 S | Av: S N2 D2 P M1 S

If a raga1 constitutes more than mere arrangements of notes derived from a given scale, this is due to the mood it evokes in listeners from different backgrounds. This shared experience is often explained in terms of “colour, beauty, pleasure, passion and compassion”, the very connotations of the Sanskrit root ranj from which rāga is derived.

Many scholars have probed into such associations, some shared across India and depicted in countless miniatures, carrying a specific connotation (for a given community of practitioners), or relating to regional customs.

So innovation – including new ragas and adaptations from other cultures – has been a matter of prestige for centuries, thereby confirming a common human trait: innate curiosity giving rise to open-mindedness, thereby widening the scope for self-expression and intercultural collaboration (or new patronage in response to changing economic circumstances and technological advancement).

This is the common ground for vocal and instrumental music whereby neither “side” dominates the other and instead, provides scope for playful interaction. What makes such interaction special is that more often than not, it dispenses with detailed musical scores, even rehearsal; and instead, relying on memory and swift anticipation. No doubt, these are assets worth acquiring (and maintaining) for young and old alike, being useful in many fields of knowledge, and therefore worth integrating in general education.

In the present context of “learning and teaching South Indian (Carnatic) music in unconventional ways”, we may freely explore this vast scope for creativity and lifelong learning: starting from minuscule motifs, then internalizing them and eventually appreciating the achievements of revered musicians past and present including the nuances in the way they render any given raga.

It is in this spirit that you are encouraged to “fill in the blanks” by first listening to a raga rendition of your own choice, then adapt any of the previous patterns in a manner that entices you to actually practice what attracted Mahatma Gandhi to music which he loved “though his philosophy of music was different”:

In his own words ‘Music does not proceed from the throat alone. There is music of mind, of the senses and of the heart.’ […] According to Mahatma ‘In true music there is no place for communal differences and hostility.’ Music was a great example of national integration because only there we see Hindu and Muslim musicians sitting together and partaking in musical concerts. He often said, ‘We shall consider music in a narrow sense to mean the ability to sing and play an instrument well, but, in its wider sense, true music is created only when life is attuned to a single tune and a single time beat. Music is born only where the strings of the heart are not out of tune.’

[Bold typeface added for emphasis]

More on the present course author’s Intercultural blog >>

I have a suspicion that perhaps there is more of music than warranted by life […] Why not the music of the walk, of the march, of every movement of ours, and of every activity?

Mahatma Gandhi in a letter to Rabindranath Tagore’s son

Rathindranath Tagore – quoted by Gopalkrishna Gandhi (p. 568):

The Oxford India Gandhi: Essential Writings

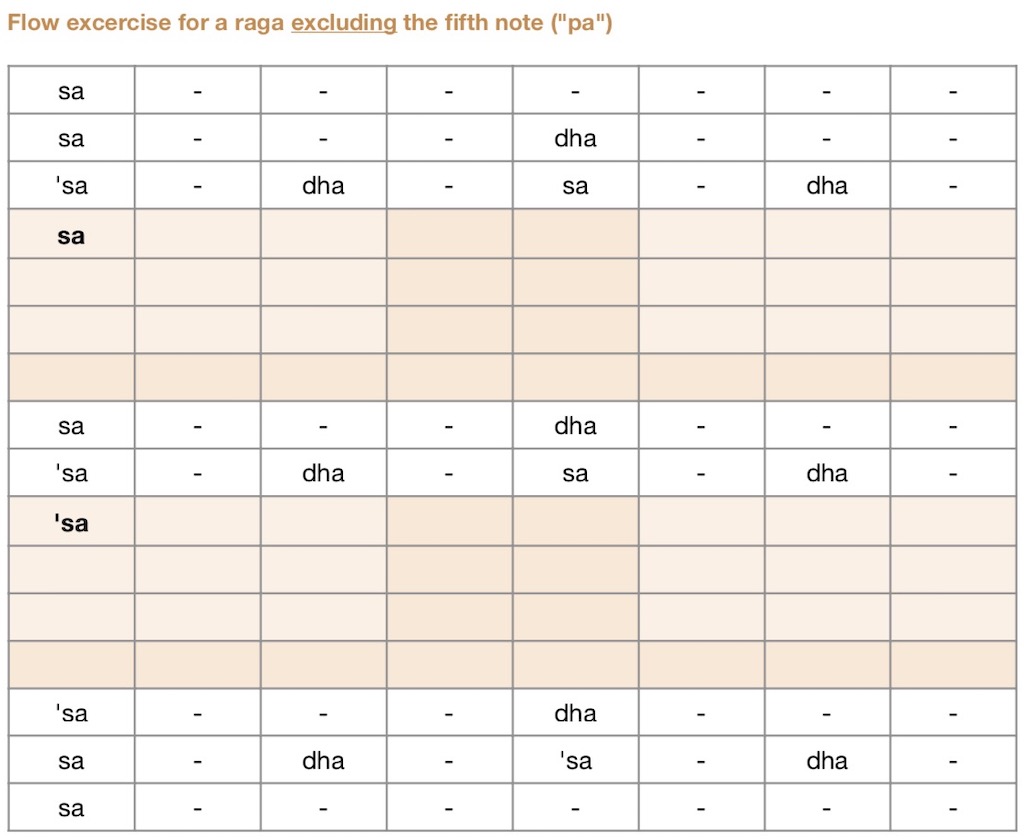

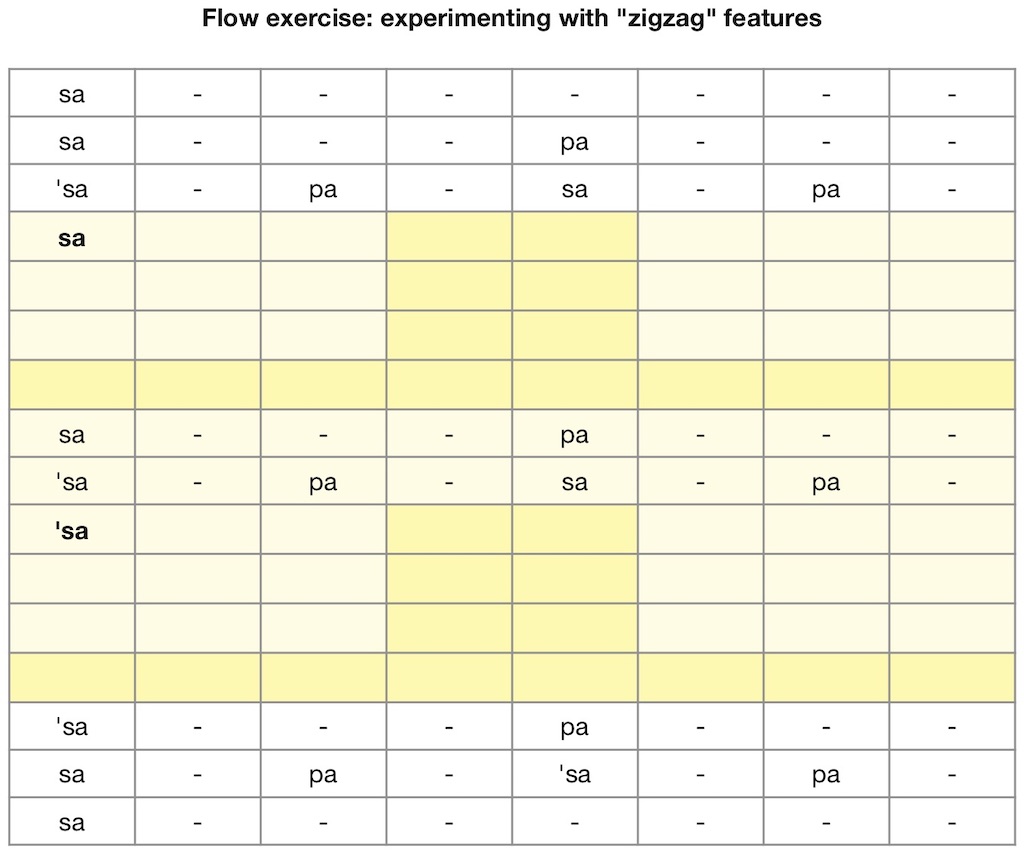

copy and fill the above table (fields marked in green)

as seen in other “Flow” exercises on this course website >>

(from a group of ragas known as pancama varja ragas), use the above table

Information about the persons, items or topics

Research & Custom search engines

The Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music

Learn & practice more

A brief introduction to Carnatic music (with music examples and interactive map)

Bhava and Rasa explained by V. Premalatha

Free “flow” exercises on this website

Introduction (values in the light of modernity)

Video | Keeping tala with hand gestures: Adi (8 beats) & Misra chapu (7 beats)

Why Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever

Worldcat.org book and journal search (including Open Access)

- The most concise definition of a raga may be that by Joep Bor: a tonal framework for composition and improvisation. [↩]