Whether you learn singing, practice a melody instrument or seek a better understanding of your favourite music – it’s the proverbial saptasvara “seven notes” that provide the key to the Unity in Diversity that sets Carnatic music apart:1

sa ri ga ma pa dha ni

One point to remember in the present context is that musicians are free to choose any pitch as basic “sa” (ādhāra sadja) to which they adhere throughout a practice session or concert.2

Another important point to remember: experienced musicians render certain notes in a plain fashion (easily identified as “pitch”) while others are embellished to the extent of blending into one another (no longer heard as “pitch” as in Western music)3.

Depending on the raga practiced, all the seven notes may be sung or played (as in Mayamalavagaula, usually the first raga taught to learners) whereas one or two may be avoided altogether in another raga, for instance in the popular ragas Sriranjani, Mohana and Hamsadhvani which figure among the present “Flow”-series of exercises.4

Practicing these notes in multiple ways5 enables you to become a discerning listener (rasika) capable of appreciating a unique raga rendition by a particular vocalist or instrumentalist.6

For centuries teachers, composers and dance masters have relied on the articulation and notation of musical notes in ways that kindle creativity and cultivate memory while attuning themselves with a particular occasion, season or time of the day.7

The ability to identify these notes and render them with feeling (bhava) is as indispensable for daily practice as it is useful for cultivating memory in such a way that it lends itself to become part of one’s daily routine: brief practice sessions to be enjoyed anywhere, any time – whenever you may spare a few minutes for something special, music embodied beyond distraction.

So let’s get into the flow and appreciate the fact that today, Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever; and also appreciate the above mentioned nuances, to begin with by listening attentively to Sreevidhya Chandramouli who recorded the famous gitam (didactic song) in raga Malahari by Purandara Dāsa for the benefit of all learners.

Time for some practice with scope for self-expression and adaptation8

- Flow | Mela practice

- Flow | The right tempo or “Kalapramanam”

- Flow | Mela practice – svara pairs

- Flow | Mela practice – svara pairs (3 counts)

- Flow | Mela practice – number patterns (3 counts)

- Flow | Janya practice 6 notes

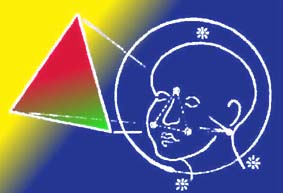

- Flow | Moods, feelings and colours

- Flow | Janya practice 5 notes

- Flow | Janya practice 5 notes – raga Hamsadhvani

- Flow | Janya practice 5 notes – raga Valaji

- Flow | Janya practice 5 & 6 notes – raga Vasanta

- Flow | Janya practice 5 & 7 notes

- Flow | Practicing “mela pairs”

- Flow | Colourful and creative “when life is attuned to a single tune” – Mahatma Gandhi

- Flow | And what about rhythm? – Let’s go on a musical walk!

- Flow | Participating for the joy of it

Practice goal and some tips: become fluent in the use of svara syllables; here arranged as tiny melodic figures for frequent repetition; to begin with, each note should be articulated clearly and with feeling while paying attention to slow, gentle yet deep breathing (without need for measuring or “keeping tala”).

This may be followed by practice based on Adi tala: 1 syllable per count as seen in each exercise, eventually doubled and quadrupled to 2 and 4 syllables per count as in a traditional course of Carnatic music (abhyasa ganam). To make your practice even more effective and enjoyable, listen and pay attention to the way an experienced performer connects and embellishes the notes associated with the raga you have chosen to practice.

Please note

The exercises presented here are inspired by those found in the standard syllabus (abhyasa ganam) attributed to 16th c. composer Purandara Dasa. Just as traditional exercises for beginners, the present ones cover a vocal range not exceeding the proverbial “seven notes” (saptasvara), likewise rounded up by one extra note – the basic note sa (sadja), now sung an octave above the starting note:

sa ri ga ma pa dha ni ‘sa

sa = middle octave (madhya sthayi), ‘sa = higher octave (tara sthayi)

whereby one or several notes may be omitted

in a given “derived” (janya) raga based on

5 or 6 notes, some combining 5 or 6 notes with 7 notes

(i.e. in the basic ascending or descending scale pattern)

Tradition and change: integrity matters, even in the digital age!

In this course, new exercises are introduced with due respect for integrity – respect for a music that has evolved over several centuries (in its present concert format) and far beyond (as regards thought provoking concepts that kindle long-term immersion).

Some of the exercises and methods facilitate continuous or frequent practice among learners who struggle with multiple commitments.

So this is all about the kind of active involvement in a tradition wherein music is simply indispensable for leading a fulfilled life. This also explains why long-term commitment is compatible with socio-economic and scientific change. This calls for imagination, a fact reflected in text books that highlight the importance of manodharma sangita, a concept reaching beyond “improvisation” as understood in Western music.

We may therefore safely conclude that both commitments, learning and teaching, are by no means determined by an individual’s station in life.

For this reason, lessons may either be shared regularly and personally (by a guru, in the past largely informally within a household known as gurukulam), or without personal contact by emulating an inspiring exponent – alive or otherwise (manasa guru, manasika guru). Many musical biographers and hagiographers share a conviction that a learner’s choice for either approach – personal or indirect lessons – tells little if anything about an accomplished musician’s status.

In short, this is all about dedication and integrity, even in the digital age!

Vocal range

Keeping the present series of exercises within one octave makes it easy to include female and male vocal learners in a single session.9

Another advantage for both, beginners and advanced learners, is that a limited range enables them to focus on continuity and expression. This reduces the risk of straining one’s voice even during longer practice sessions.10

An important feature of classical South Indian music is its reliance on memory. Today as in the distant past, memory is being trained with the help of vocal practice rather than resorting to detailed notation. This preference applies to singers and instrumentalists alike.11 This pragmatic approach perfectly suits a repertoire that provides ample scope for improvised interludes in virtually any type of composition, be it in regular concerts12 or arrangements performed for dance recitals, drama and film music.

“Students who get into flow as they study do better”13

Such concentration and immersion is the key to getting into flow: “A bedrock of flow is feeling completely absorbed by an activity, and that often requires a state of deep concentration.”14 For this it’s worth remembering that patience is the secret for success in any practice worth the effort!

For details on the classical music of South India (including staff notation for ragas covered in the Flow series), see the present author’s critically acclaimed reference work: The Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music >>

- The title of this essay by Ludwig Pesch refers to ‘unity’ of different traditions as understood by Indian practitioners and musicologists – notably T. S. Parthasarathy – in ‘The Unity of Indian Music’, The Journal of the Music Academy Madras: Golden Jubilee Special Number 1977 (1980 [↩]

- Rather than theorizing about such matters, however important for effective practice or pleasing raga rendition, they would point out that attentive listening is the key to proper understanding of sruti. The term sruti is commonly used for two different concepts: either in the sense of “correct intonation” or “microtonal differentiation” (as applicable to a specific raga); and more generally, in the sense of a basic note (Western tonic), the “sa” from which other notes are derived in the course of a musician’s rendition; the latter is often indicated as “1 sruti” for C (as seen on a keyboard), “2 sruti” for D, “3 sruti” for E and so forth (i.e. the 7 white keys); and “1 1/2 sruti” for C# etc. Such conventions make it hard for teachers and learners to reconcile music theory with actual practice in Carnatic music education even if the same may apply to music education in other cultures as well. A popular saying cited by V. Sriram (an authority on the recent history of this music) may resolve any awkward situation: karnataka sangitam is that which haunts the ear! [↩]

- If in doubt how this may be reconciled with the notion of precision as regards microtonal differentiation, listen carefully to the unison rendition of a varnam (raga Valaji) by noted violin duo Lalgudi G.J.R. Krishnan & Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi. [↩]

- Listen to (1) Uma Ramasubramaniam rendering the saptasvara as taught to learners of Carnatic music: raga Mayamalavagaula in its pristine form; (2) vocalist Sanjay Subrahmanyan improvising in the same raga without accompaniment; (3) a brief keyboard demonstration starting from C; and (4) different performers applying the same basic notes in their performances. [↩]

- Depending on a learner’s situation, this would begin with singing variations of a particular scale (mostly that underlying raga Mayamalavagaula) thereby covering all the seven notes; and gradually progress through a series of compositions wherein “svara singing” of musical phrases alternates with short lyrics (e.g. in a varnam) distributed over the same tune during its repetition.

Such characteristics are demonstrated with great clarity by noted the singer and vocal guru Dr. Nookala Chinnasatyanarana. Listen to brief audio excerpts from a varnam lesson in raga Sankarabharanam (the first excerpt rendered with syllables, the second one with lyrics):

The practice of teaching by way of alternating solmisation (svara singing) and lyrics (sahitya) is further demonstrated in his numerous audio and video lessons, freely accessible on YouTube. [↩]

- Clear and straightforward renditions of many ragas are generously shared by Uma Ramasubramaniam on Raga Surabhi, an advertisement free website highly recommendable for all learners and lovers of Carnatic music. [↩]

- Similar techniques are used for keeping tala for Carnatic compositions and – to a certain extent – comparable to western solfège with one notable difference: such “solmisation” figures prominently in every Carnatic concert (or dance recital), right from the opening varnam to the complex rhythmic figures known as tirmanam and korvai that allow performers to demonstrate their virtuosity or originality. [↩]

- These exercises supplement (rather than substitute) traditional lessons and self-study. [↩]

- “The ability to traverse smoothly through the middle octave (from base Sa to higher Sa in that octave) is one range, anything above the higher Sa, which is the higher octave, is usually half octave for vocalists, as the number of svaras [musical notes] reachable are limited to Pa. Similarly, in the lower octave, the svaras reachable could be till Ma, generally. With practice, the vocal range can be improved to reach higher and lower respectively. It is advisable to do these exercises under the guidance of a Guru to avoid permanent damage to the vocal cords.” – Step 3: Identify Your Vocal Range (Date Accessed: 11 July 2023), Acharyanet.com [↩]

- If unsure what your vocal range is right now, consider testing it on the following vocal range test page to find the pitch for your basic “sa” (e.g. G#2 for joint practice by male and female voices as heard in lessons recorded by S. Ramanathan just as Nookala Chinnasatyanarayana and Sarada Krishnajee) – doing so is both useful and fun:

https://singingcarrots.com/range-test

Even though Indian performers have little use for the “A440” standard pitch (being the reference frequency for Western orchestras, see Wikipedia), the above vocal range test is useful for giving an approximate value to students of Carnatic music.Once identified, remember the pitch chosen as basic “sa” for future practice sessions; and don’t hesitate adjusting it again as and when needed. This is what renowned Indian singers have done throughout their careers: for live and studio recordings, M.S. Subbulakshmi chose F# and G as basic “sa”, like Kiranavali Vidyasankar who is also heard singing with G# on another occasion. Likewise, Vijayalakshmy Subramaniam chose G and G# (as in recordings accompanying the book Apoorva Kriti Manjari and in her “Gopala Baalam” album respectively). By comparison, Aruna Sairam seems to have preferred singing with F as basic “sa”.

Male singers have likewise vary as regards their basic “sa”: Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer chose B and C, S. Rajam and Balamurali Krishna C, and Nedunuri Krishnamurthy a slightly higher C#, and D.K. Jayaraman D# (going by his 1975 live recording). On the other side of the spectrum, M.D. Ramanathan sang in an unusually low range as far as Carnatic singers are concerned: G# for basic “sa”. Similar variations also mark the vocal ranges of male Hindustani singers like Kumar Gandharva (F#) and Bhimsen Joshi (C#), and are likely to be discernible among female Hindustani vocalists as well.

Tip: bookmark the above vocal range test page, then keep it open while listening to your favourite musicians; this allows you to check whether a particular singer’s basic “sa” suits your own vocal range for the purpose of daily practice. [↩] - Rather than resorting to detailed musical scores (sheet music), Indian musicians and composers prefer svara notation of the kind outlined here which merely serves as “shorthand“: solmization that may be written down in any alphabet purely as an aid to memory, only occasionally supplemented by symbols. [↩]

- To understand how svara singing (kalpanasvara) is integrated in a concert, listen to examples offered by renowned vocalist Kiranavali Vidyasankar on soundcloud.com/kiranavali-vidyasankar; for instance in the context of raga Sankarabharanam labelled Grand Finale (for details, read her own explanations there); this excerpt constitutes a svara-based (wordless) dialogue between the vocalist and the violinist, here from the conclusion of a ragamalika (“raga garland”) that lasts one minute before resuming the main raga, Sankarabharanam, to culminate in a series carefully calculated rhythmic figures (korvai). [↩]

- For the psychological underpinnings and potential of “flow” also in the context of “lifelong learning”, see Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman (New York: Bantam Books, 1995), pp. 106-8: “Students who get into flow as they study do better, quite apart from their potential as measured by achievement tests. […]

Who does not recall school at least in part as endless dreary hours of boredom, punctuated by moments of high anxiety? Pursuing flow through learning is more humane, natural, and very likely more effective way to marshal emotions in the service of education.

That speaks to the more general sense in which channeling emotions towards a productive end is a master aptitude. Whether it be in controlling impulse and putting off gratification, regulating our moods, so they facilitate rather than impede thinking, motivating ourselves to persist and try, try again in the face of setbacks, or finding ways to enter flow, and so perform more effectively–all bespeak the power of emotion to guide effective effort.” [↩] - Source: Jill Suttie in “Eight Tips for Fostering Flow in the Classroom“, The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley [↩]