Bookmark the present URL:

https://www.carnaticstudent.org/service/free-melakarta-raga-course/

Tips for using the slideshow

To pause/restart (autoplay) use the button seen in the right top corner (triangle/II symbols).

Please reload the slideshow or use the clear history option in your browser (to show the latest version if updated).

To forward/return to and from any slide, swipe (left/right) or click on the arrows seen on the left and right sides.

First read, then try and sing the notes as indicated.

Where “audible singing” is no option, be mindful by “singing in your mind” and get immersed – any time, anywhere!

Audio examples (for viewing with select slides)

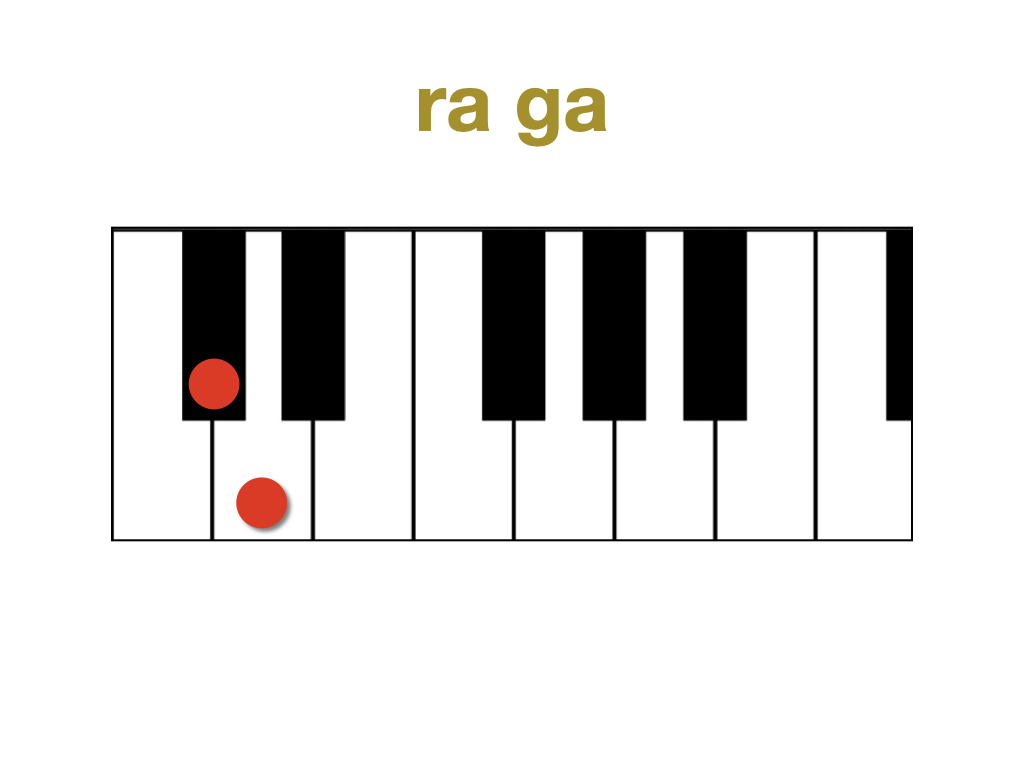

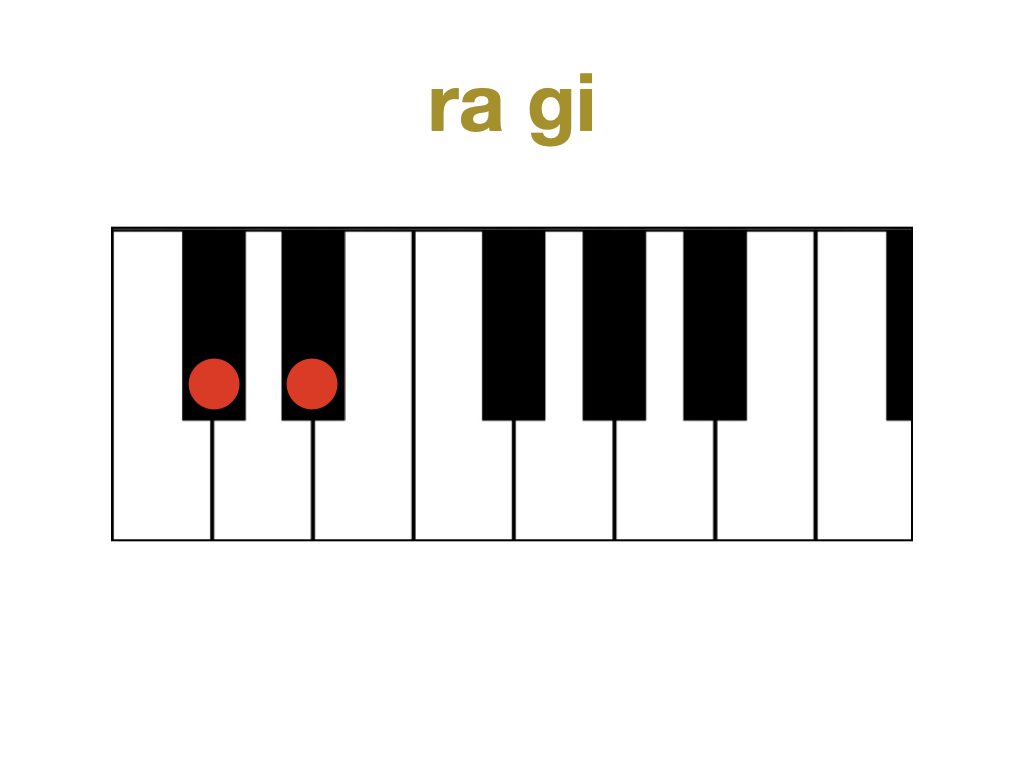

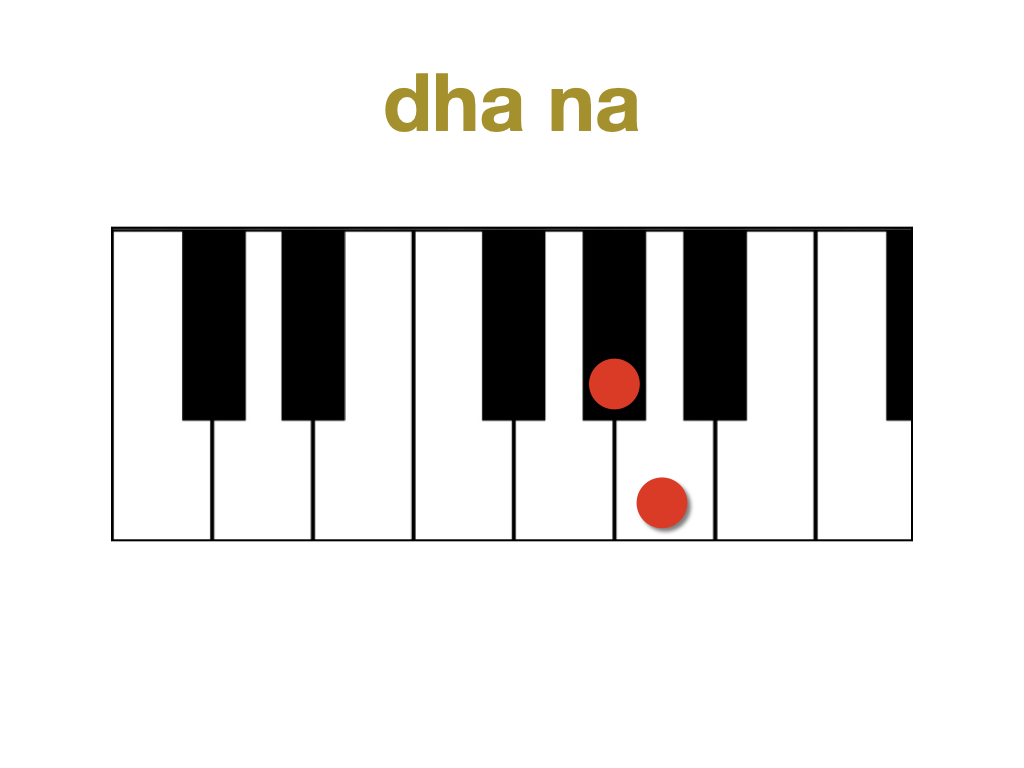

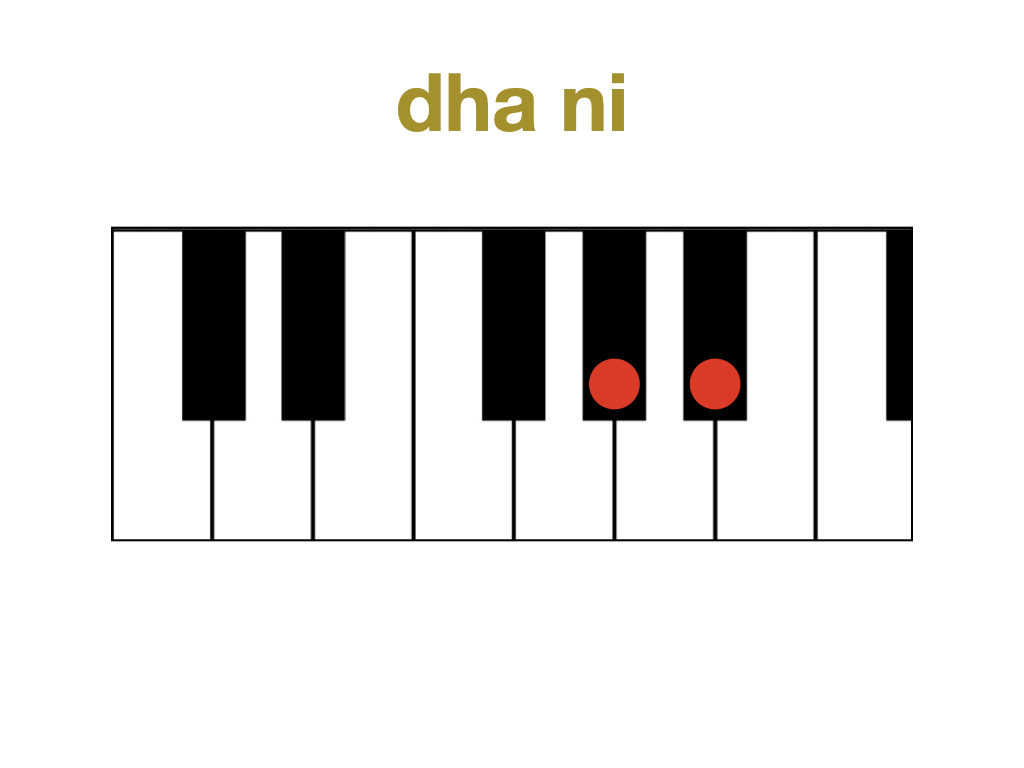

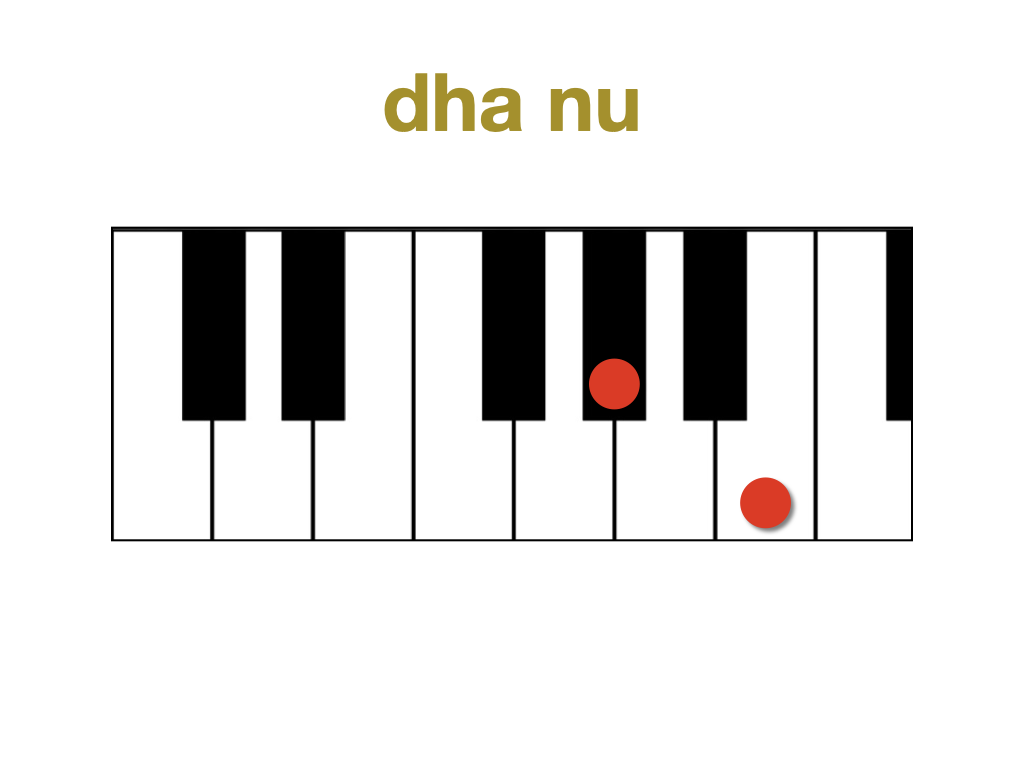

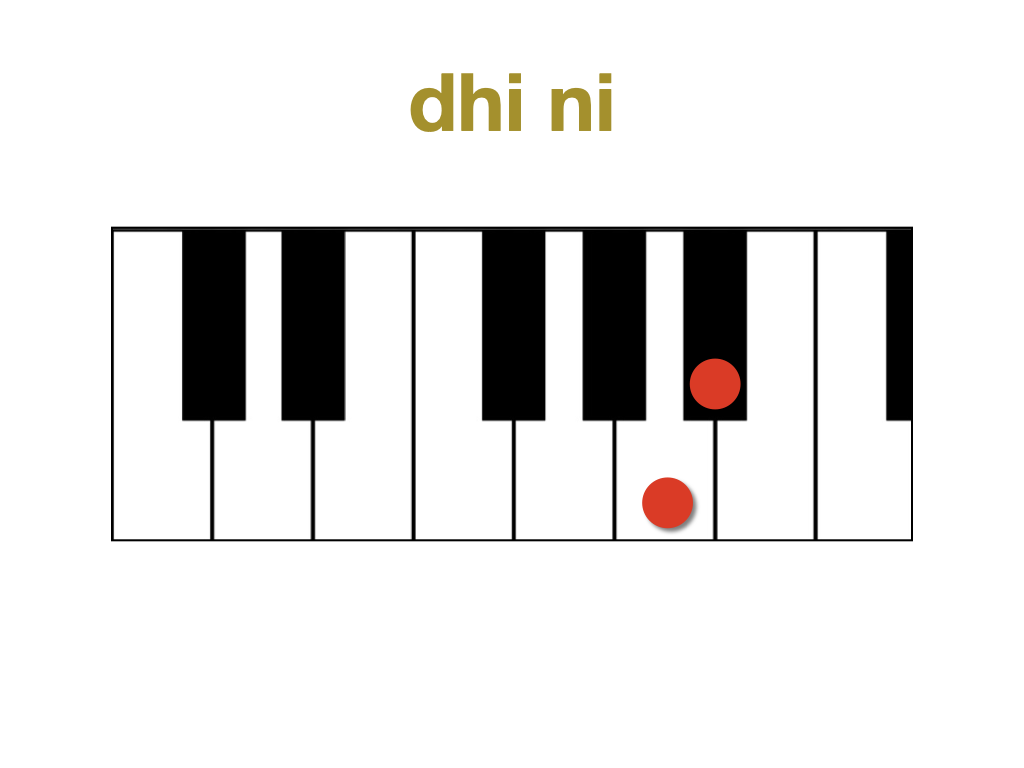

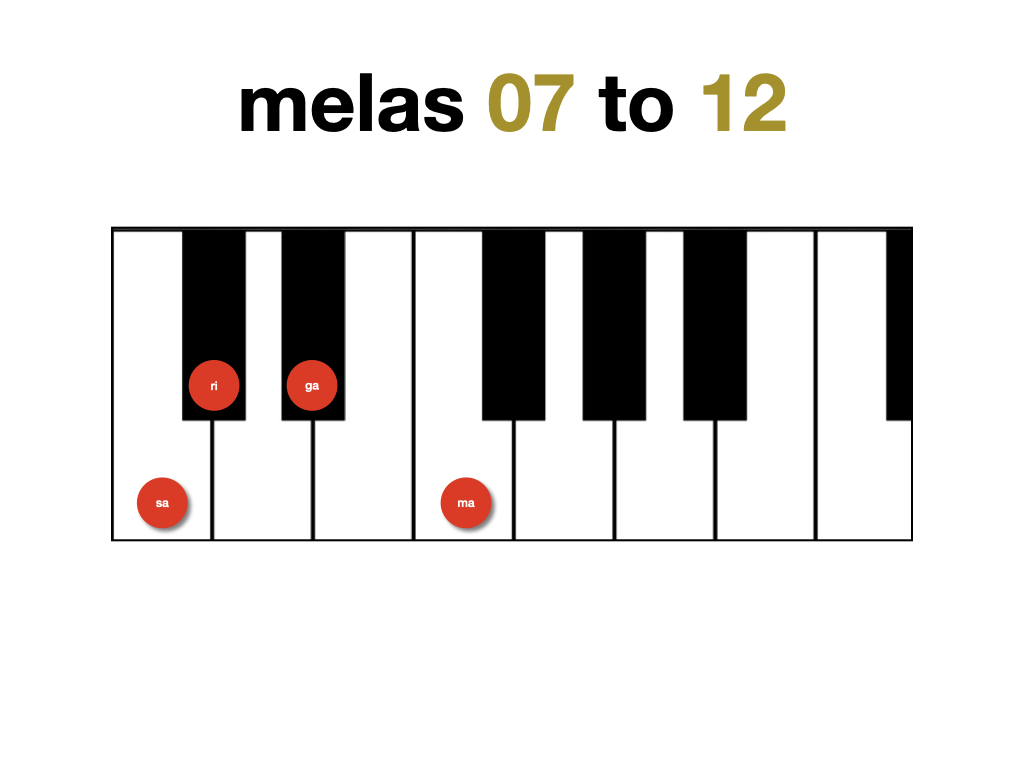

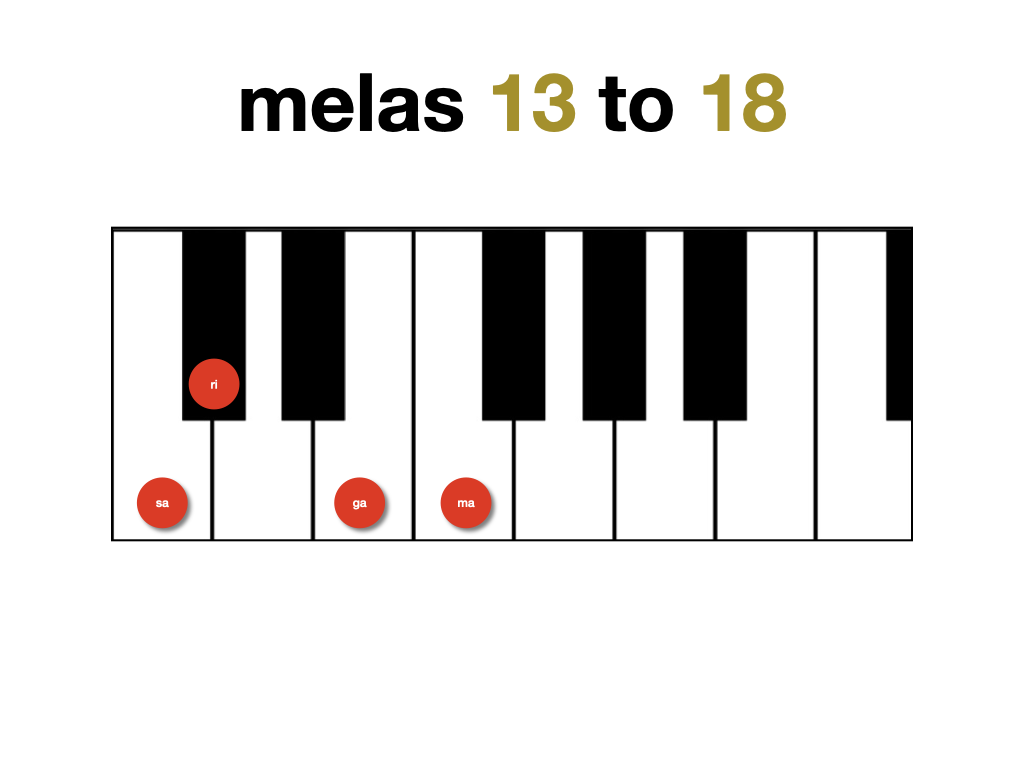

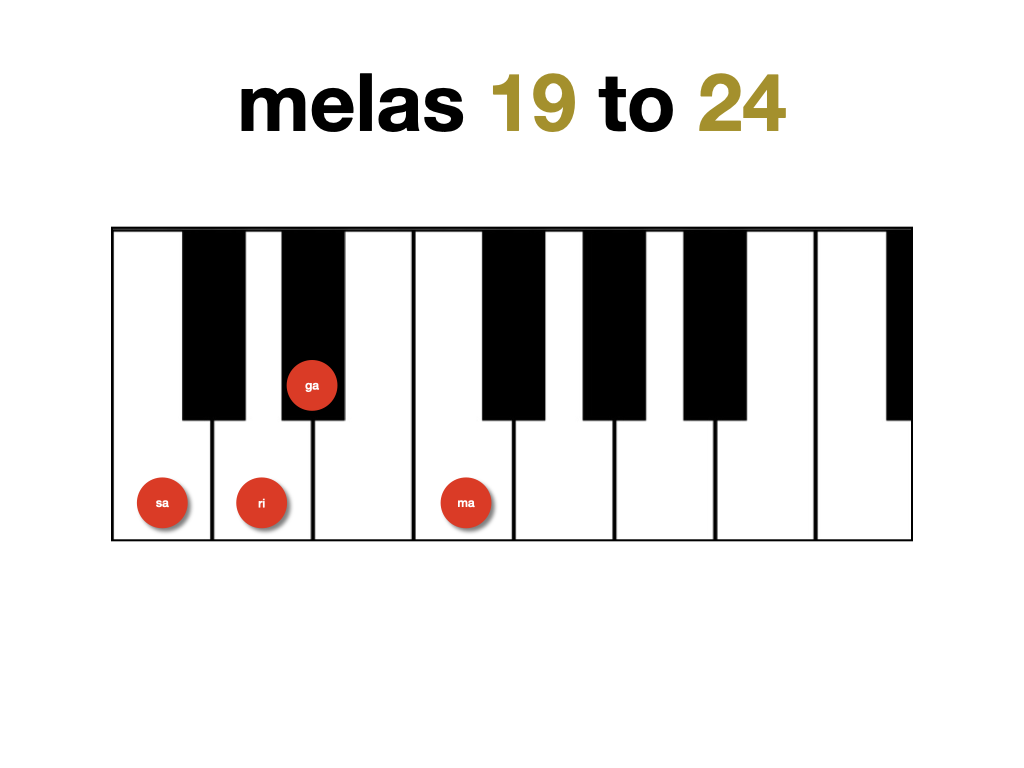

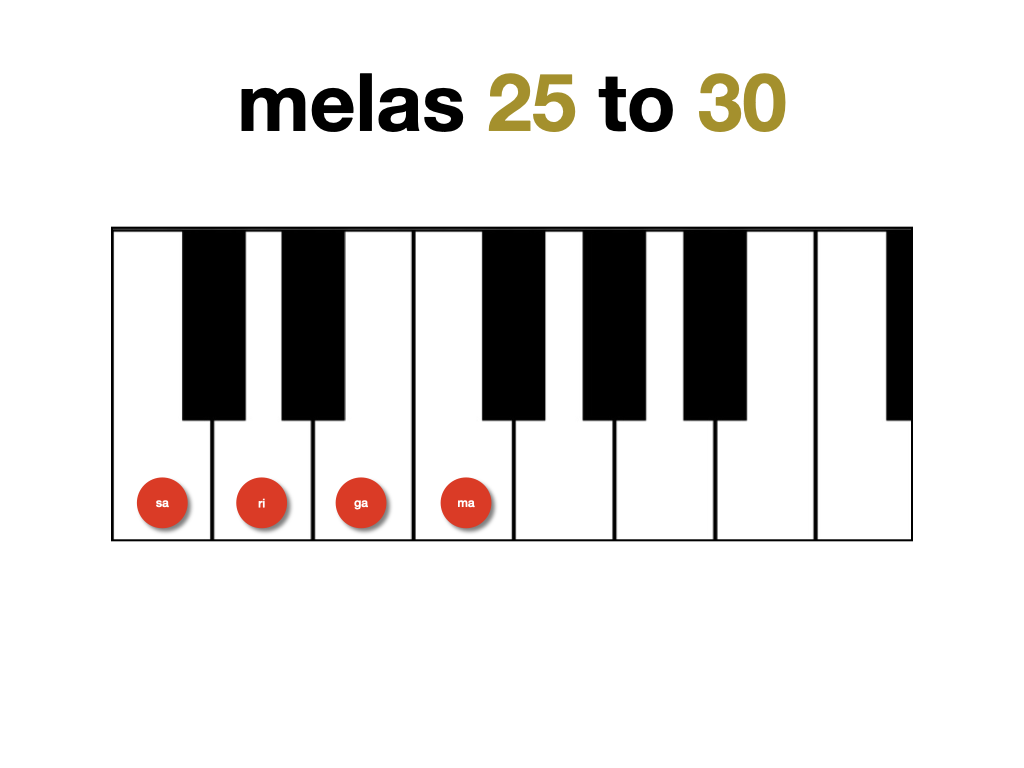

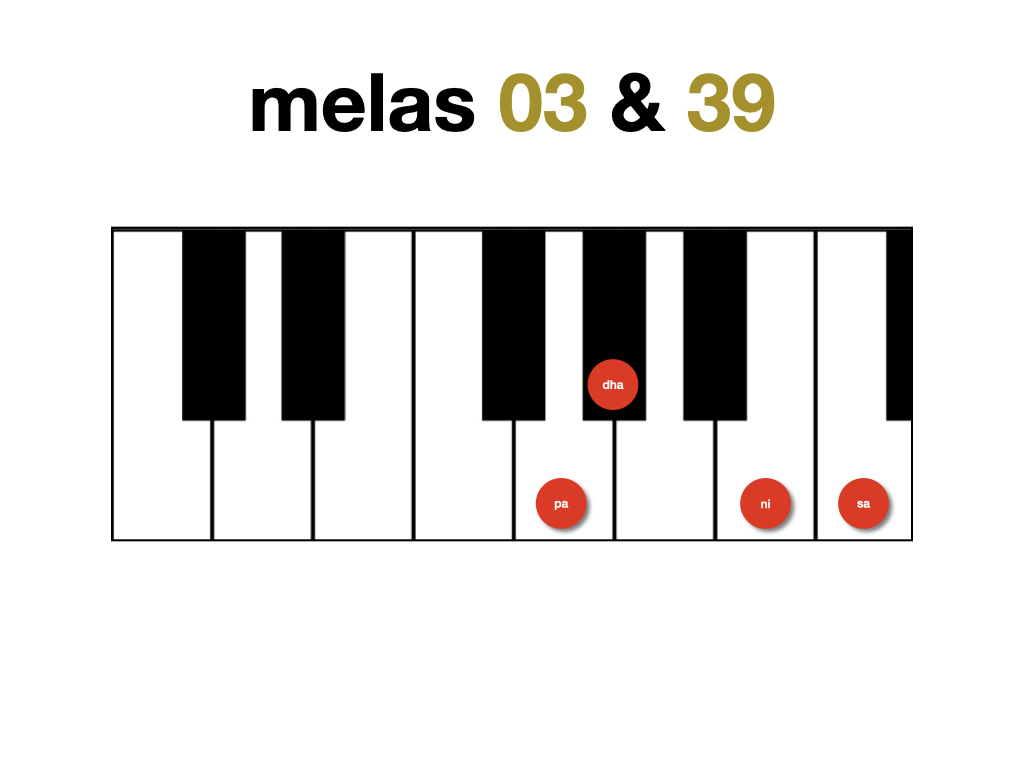

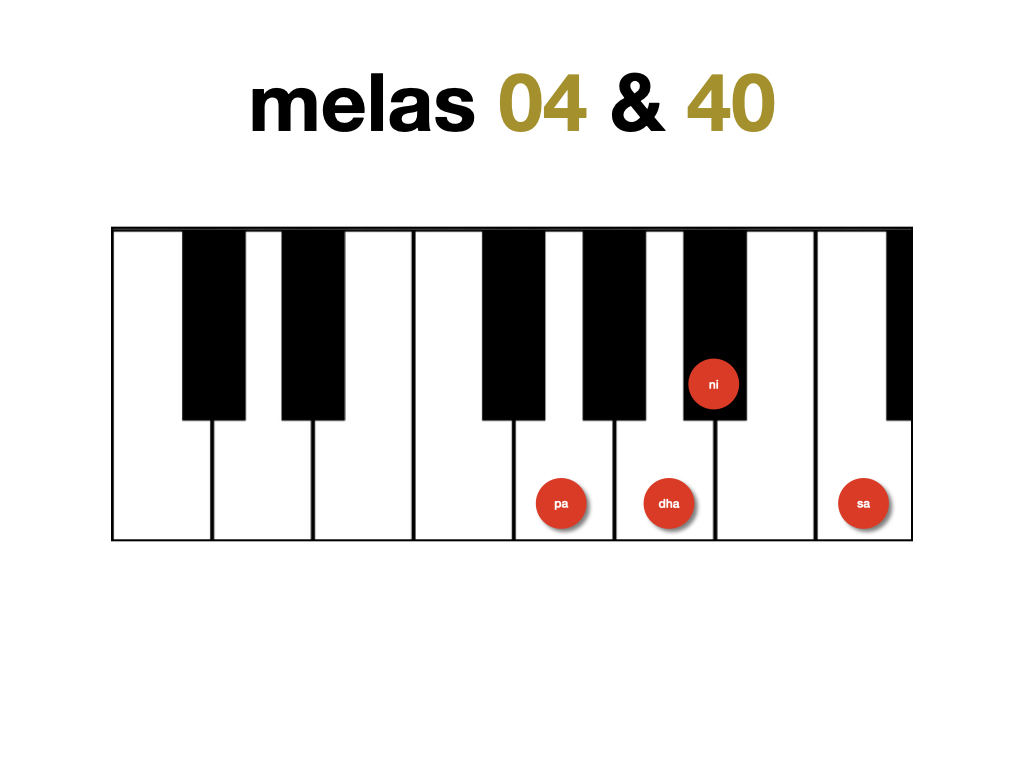

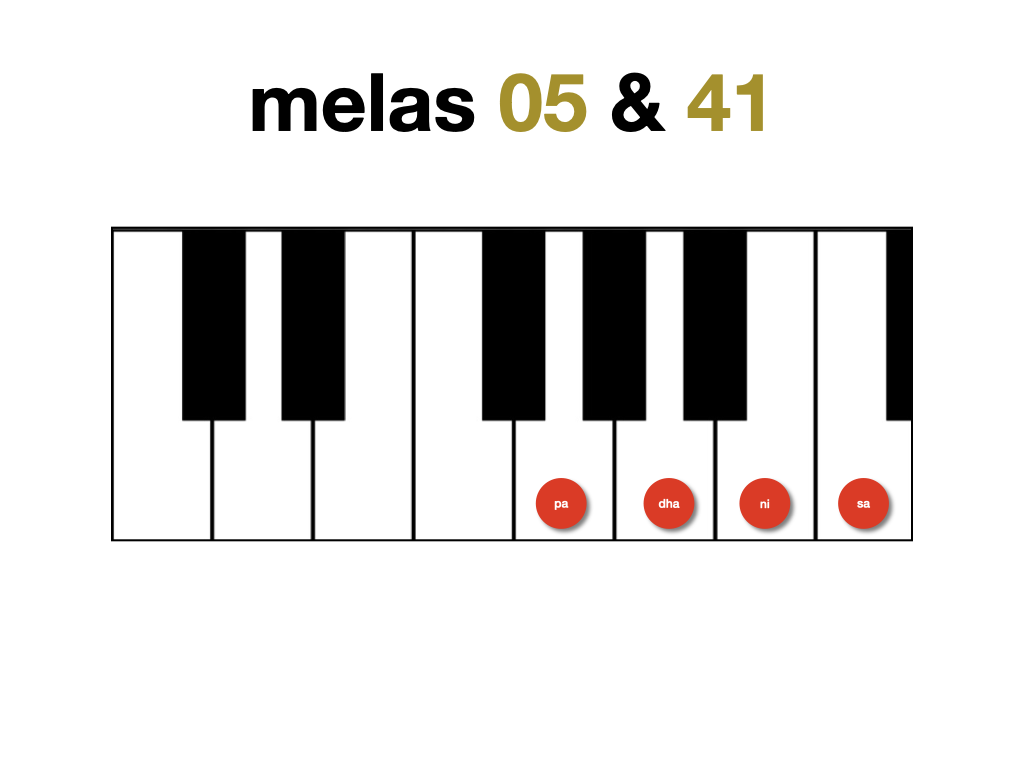

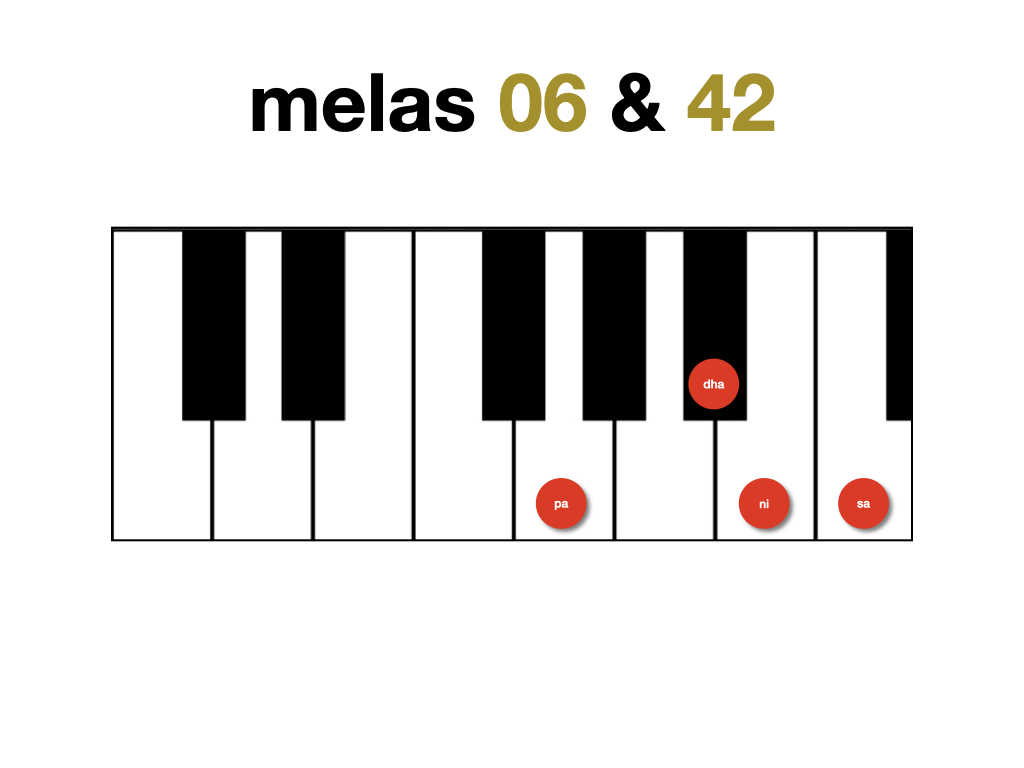

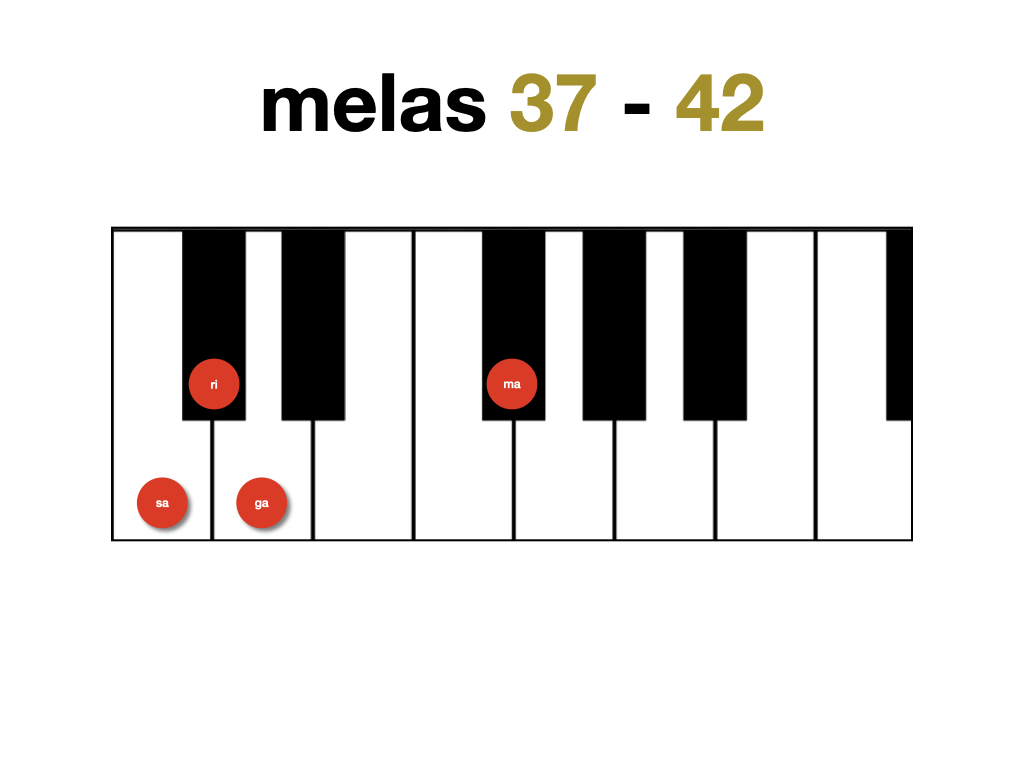

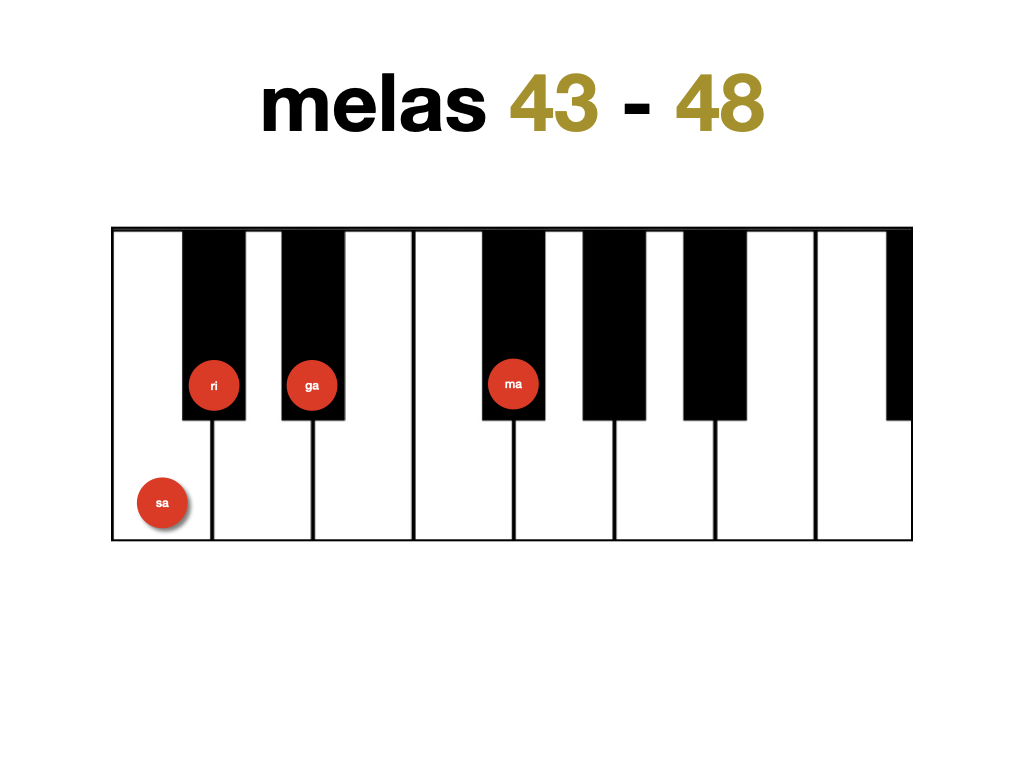

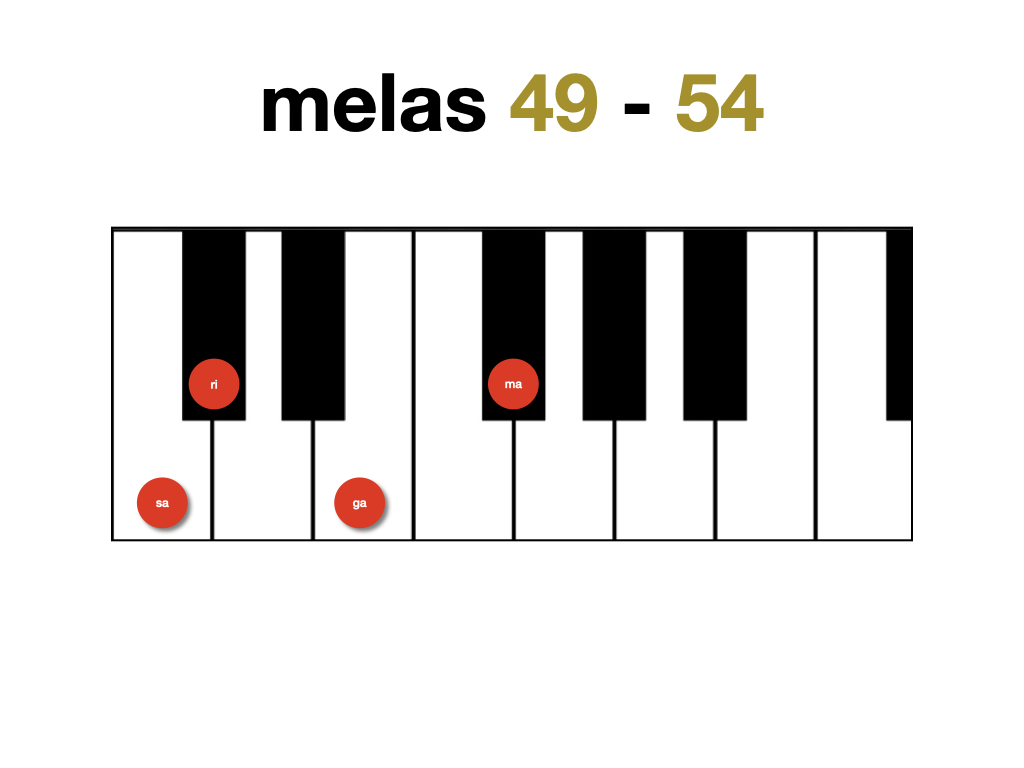

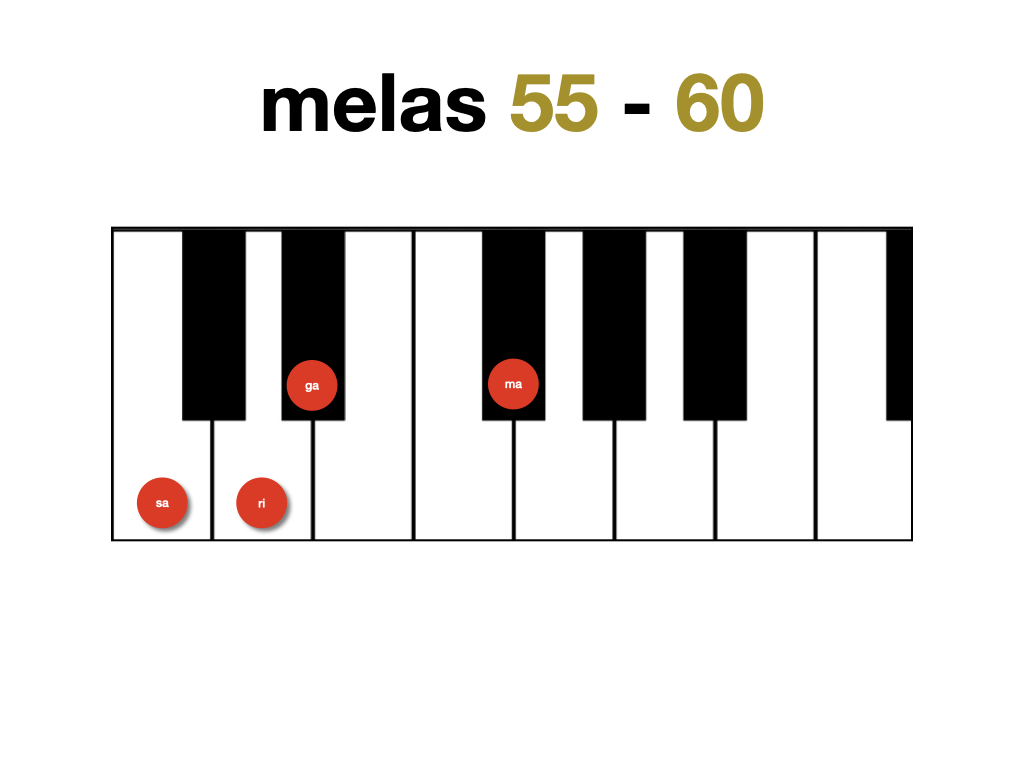

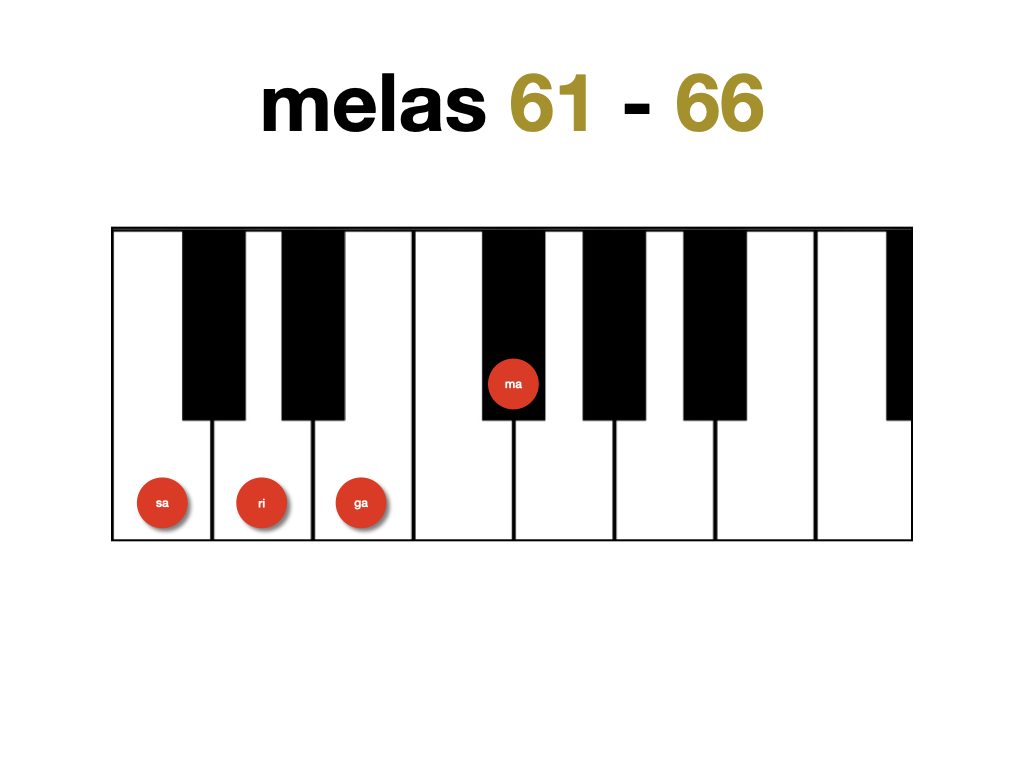

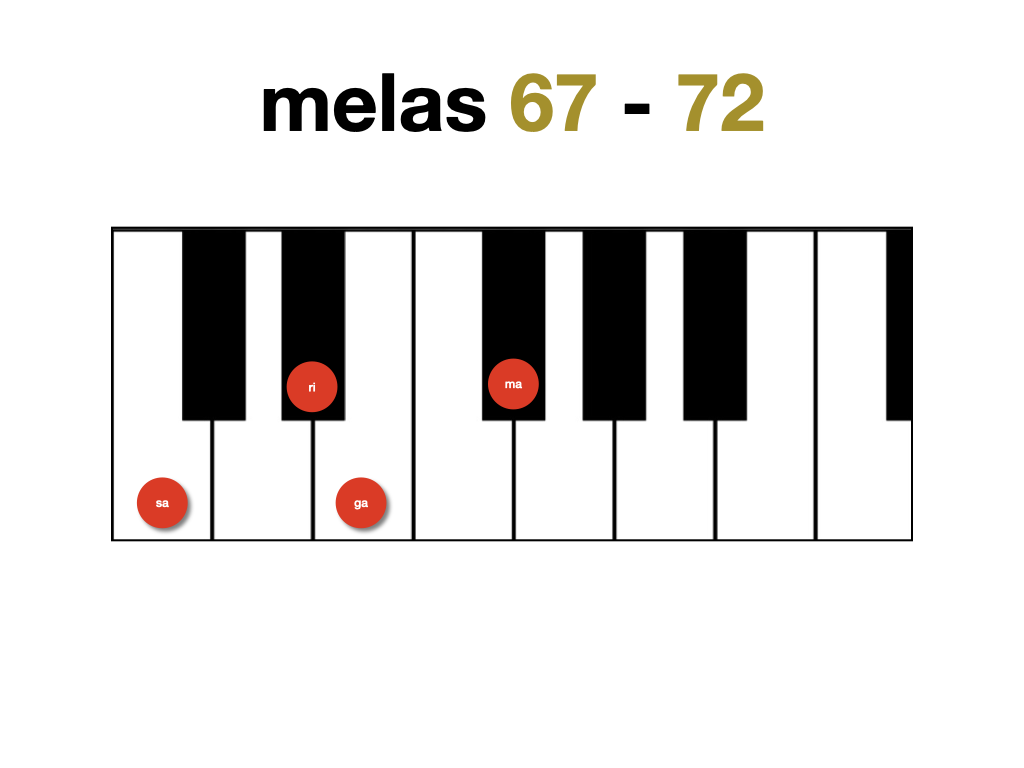

On the keyboard-patterns and midi-sounds

Please note

The key patterns and midi-sounds shared here convey a general idea, which is useful for learners familiar with western keyboards. This explains why Sangita Vidvan S. Rajam let students accompany his lecture-demonstration with a simple keyboard. He knew that the nuances of intonation (sruti) and proper embellishments (gamaka) would follow naturally by practicing together and at home, and by listening to experienced musicians from various traditions.

So keep in mind that the keyboard patterns seen here are not meant to indicate any specific pitch or “micro interval” with particular ragas.

In other words, musical nuances call for years of careful listening and practice to be expressed properly. Today just as in the distant past when Carnatic music acquired the status of a “classical” (refined and dignified) art in its own right, be it for personal fulfilment or public performance as part of concerts, dance recitals and on festive occasions.

In the words of musicologist S. Seetha, Venkatamakhi’s mela arrangement “is intended to visualise all the desi (regional) ragas which differ from place to place, from people to people and which according to the suitability of the voices, must be utilised for practical purposes.” – Tanjore as a Seat of Music (During the 17th, 18th and the 19th Centuries), p. 434

For a masterful demonstration of this concept, listen to Audio | Live concert by Bhushany Kalyanaraman >>

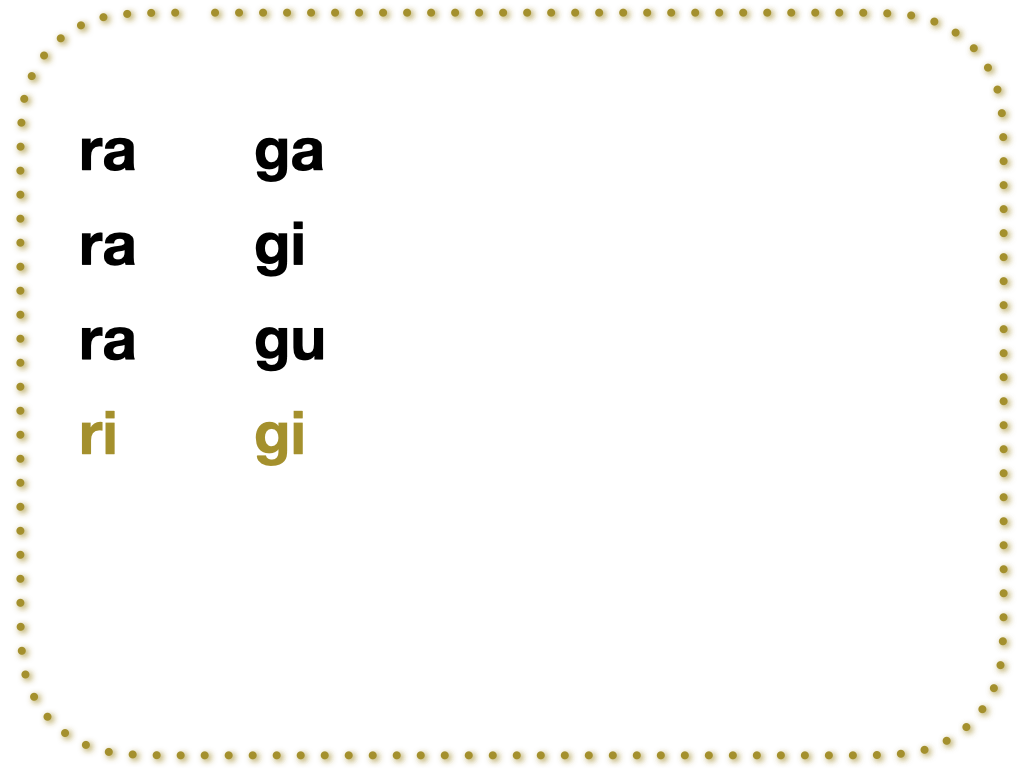

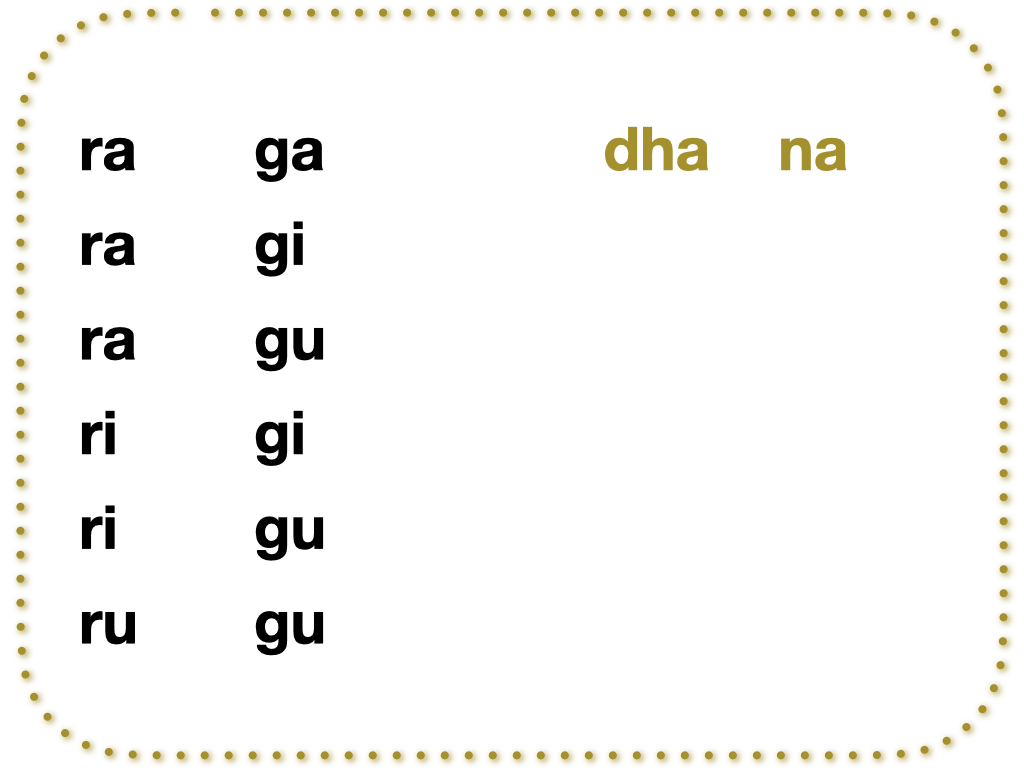

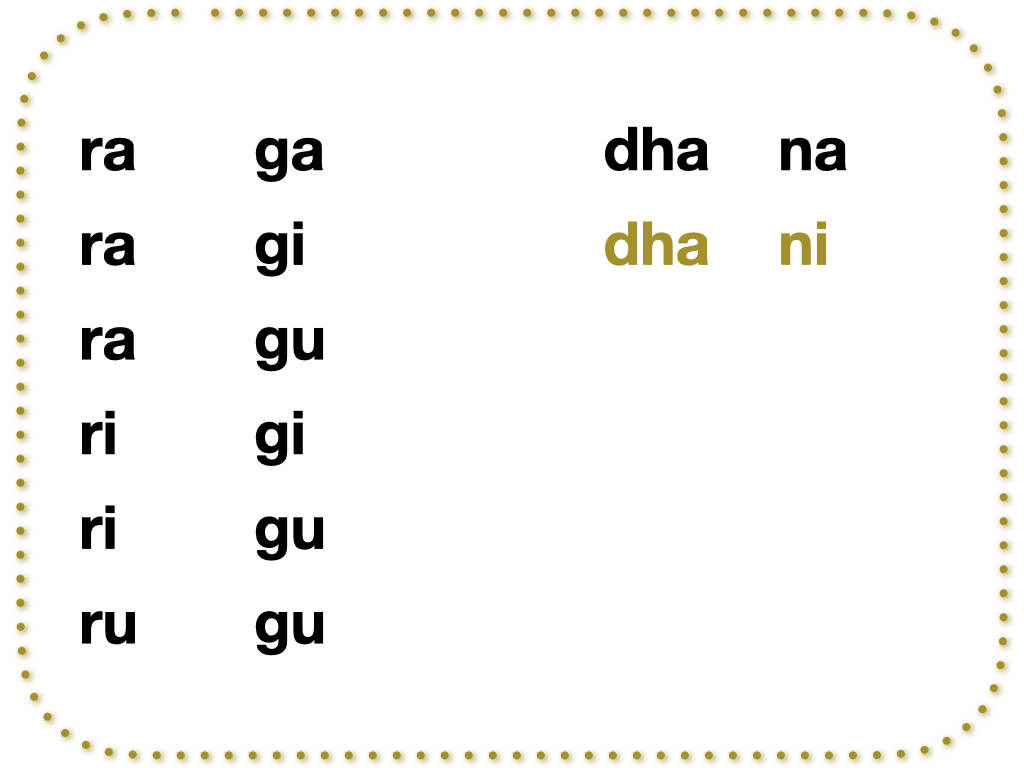

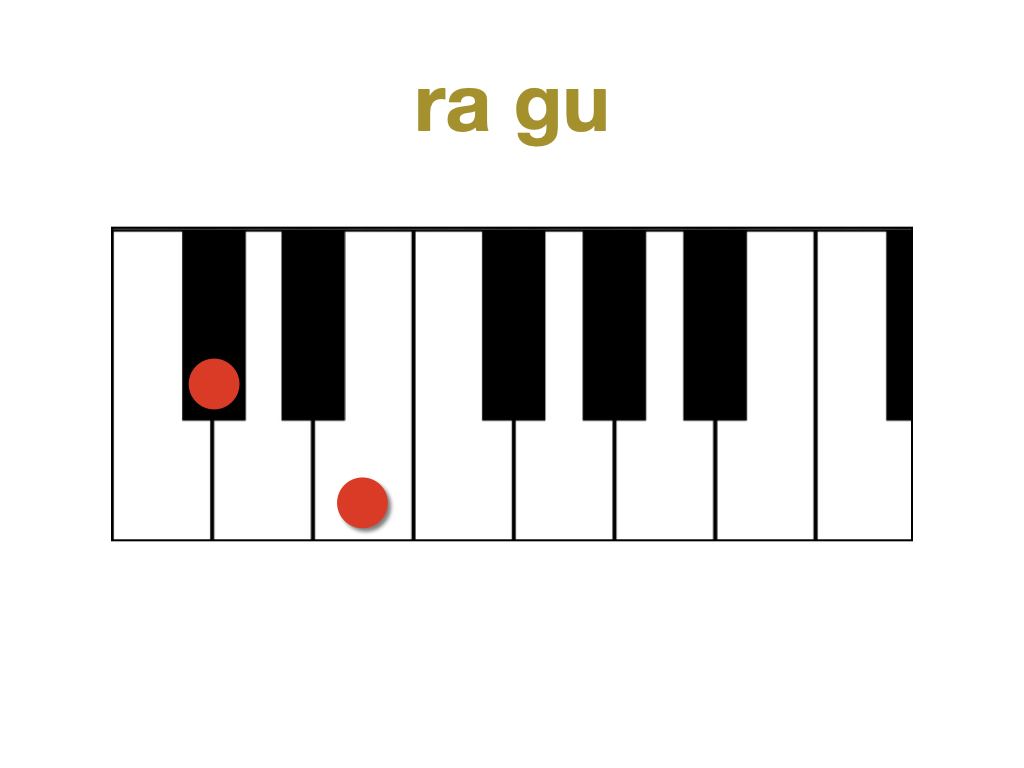

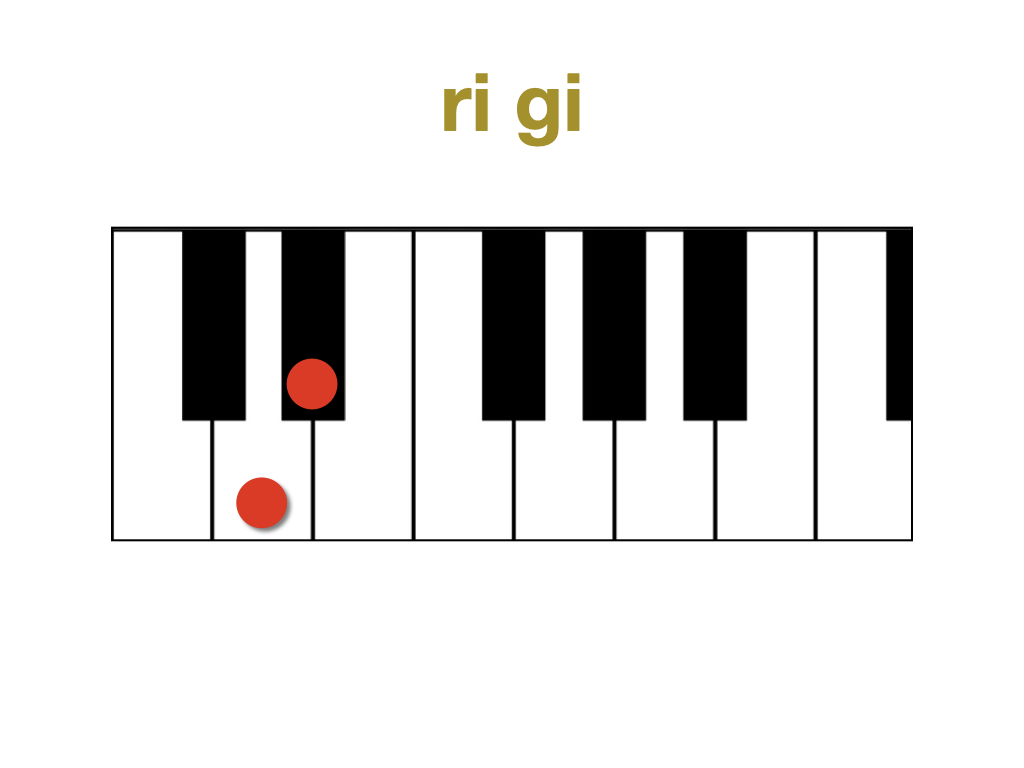

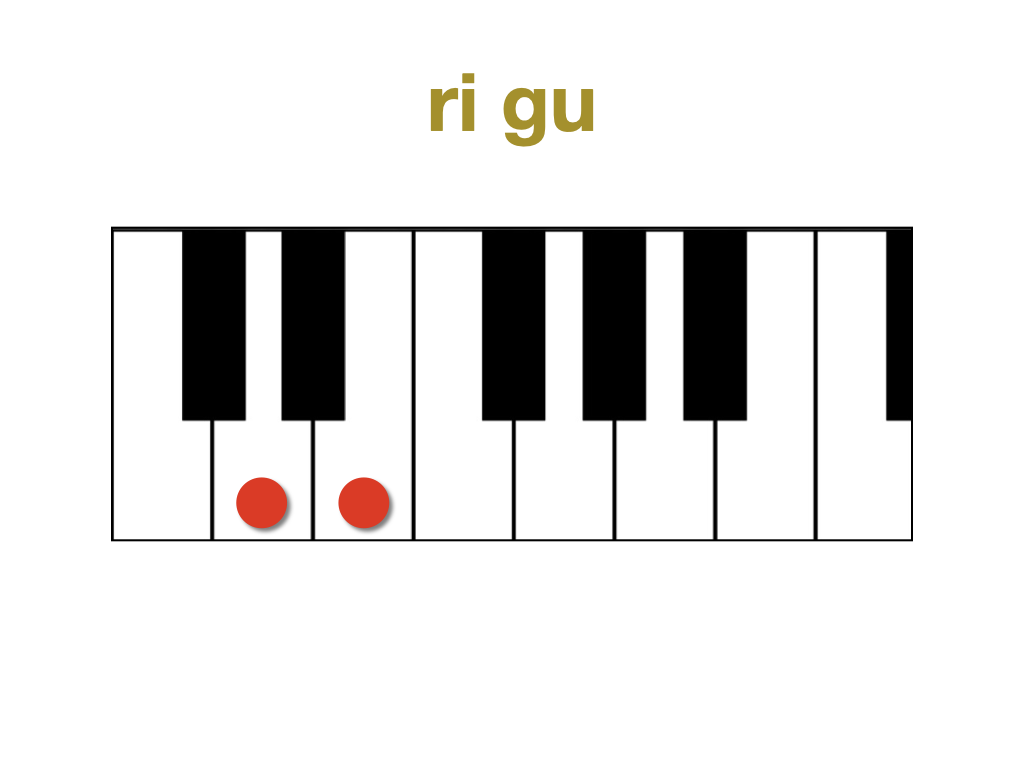

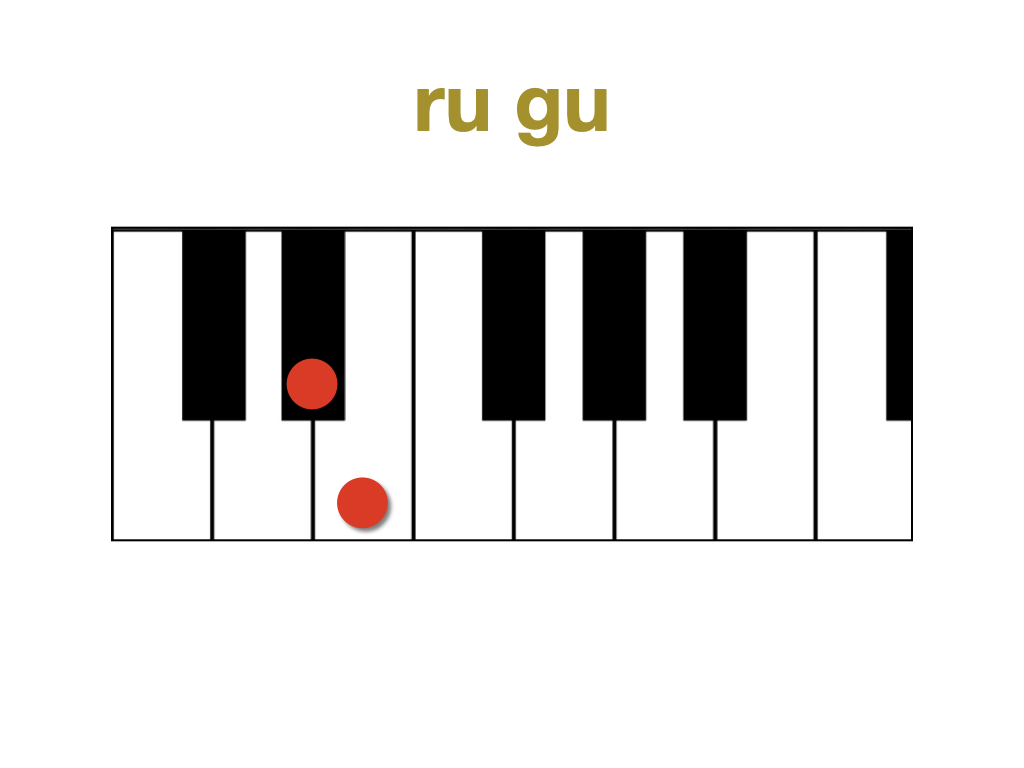

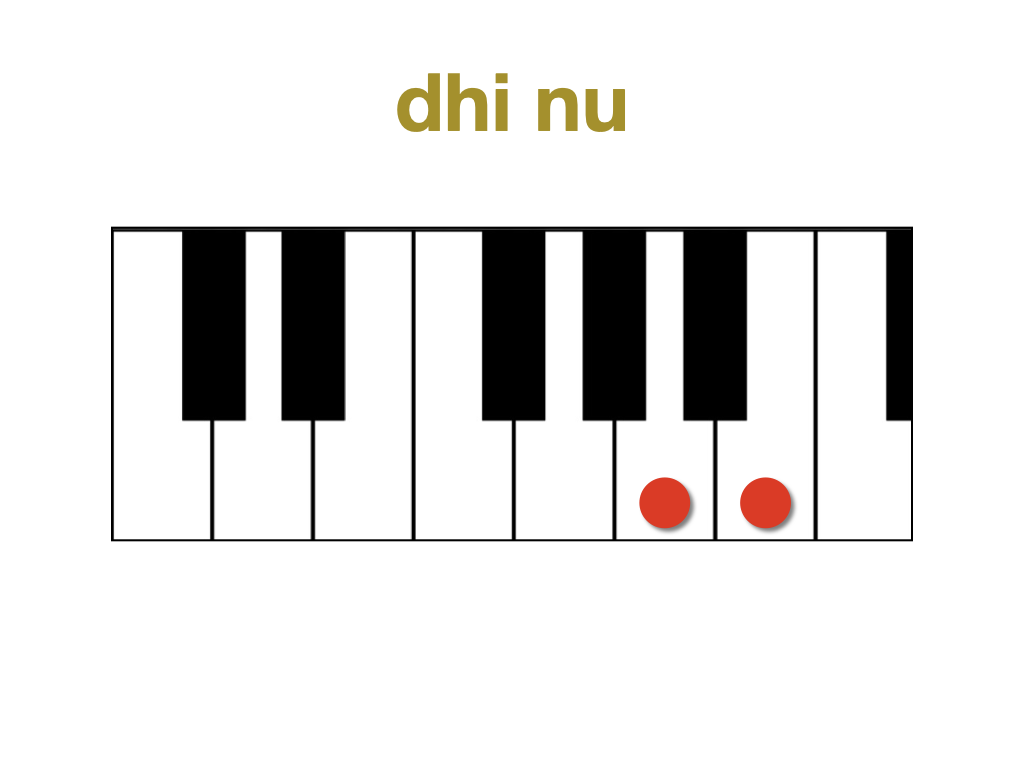

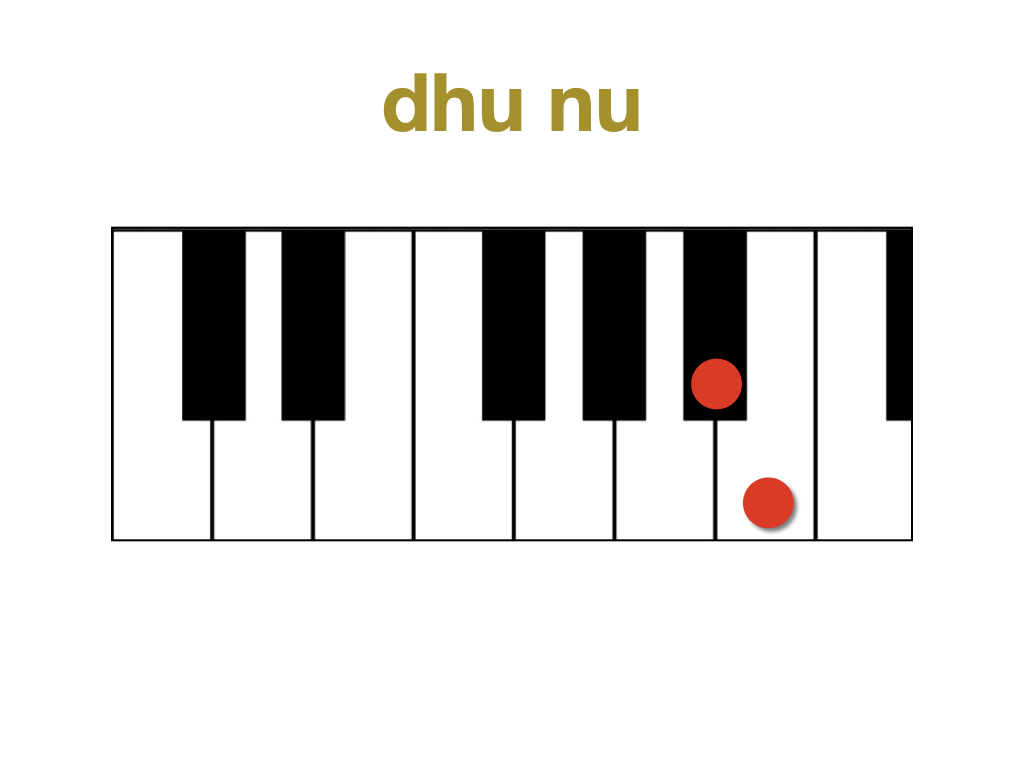

Of special interest here are the elaborate expositions of raga Simhendramadhyamam (mela 57, vowel mnemonics “Ri-Gi-Mi-Dha-Nu”) and raga Sankarabharanam (mela 29, vowel mnemonics “Ri-Gu-Ma-Dhi-Nu”)

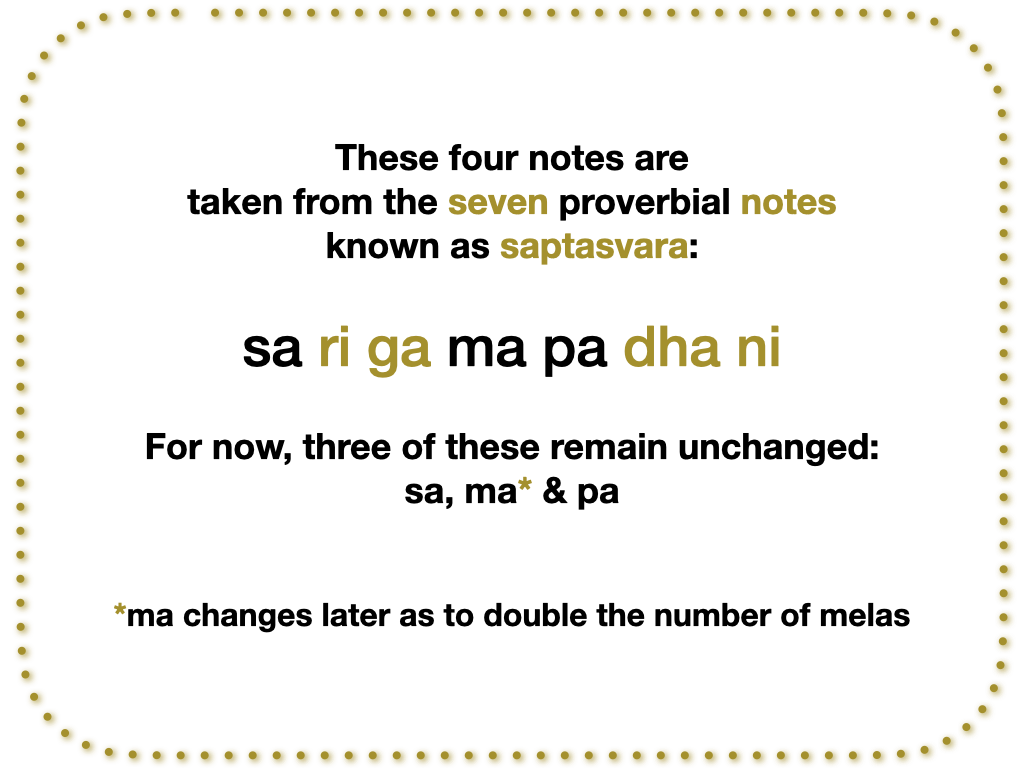

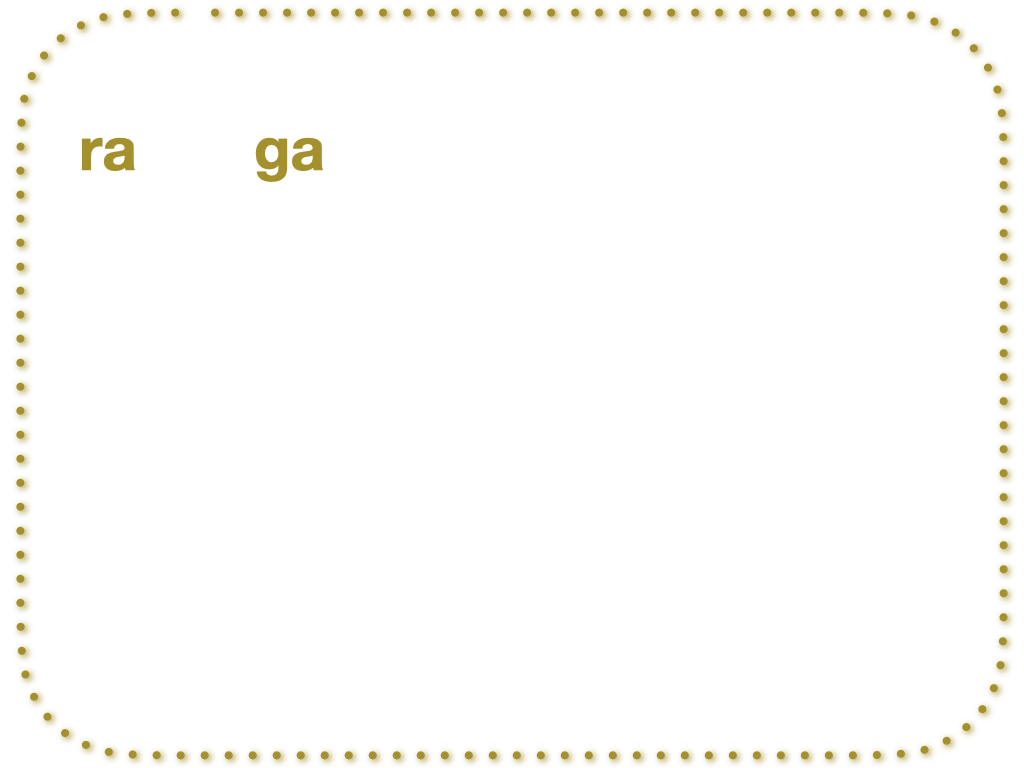

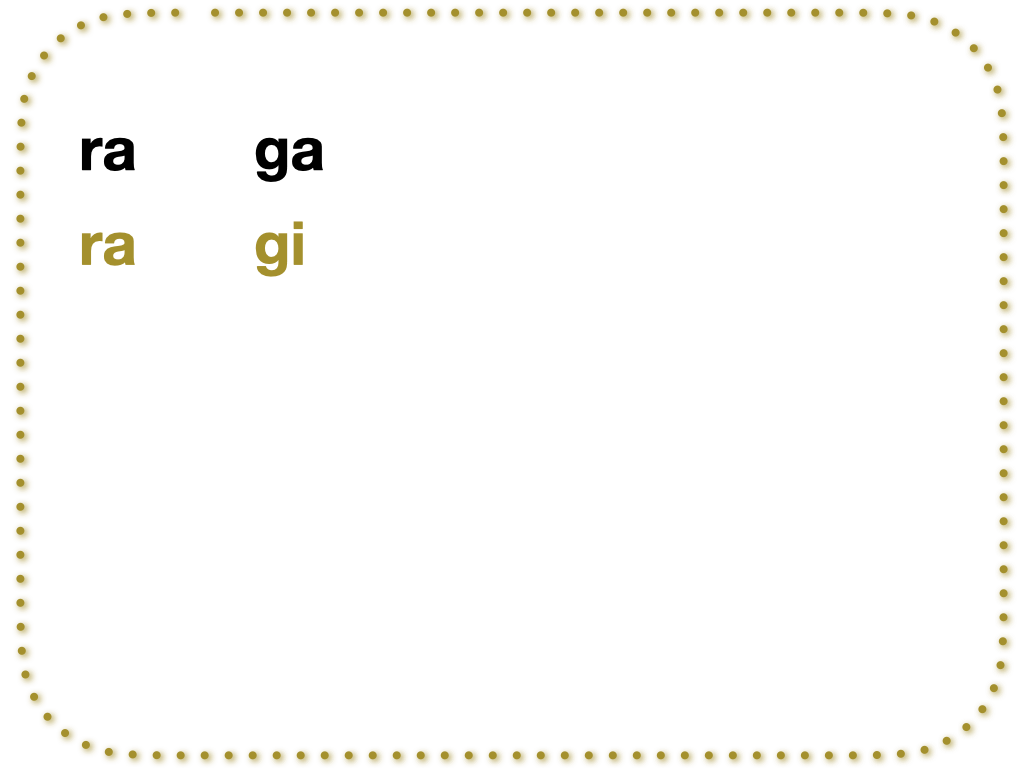

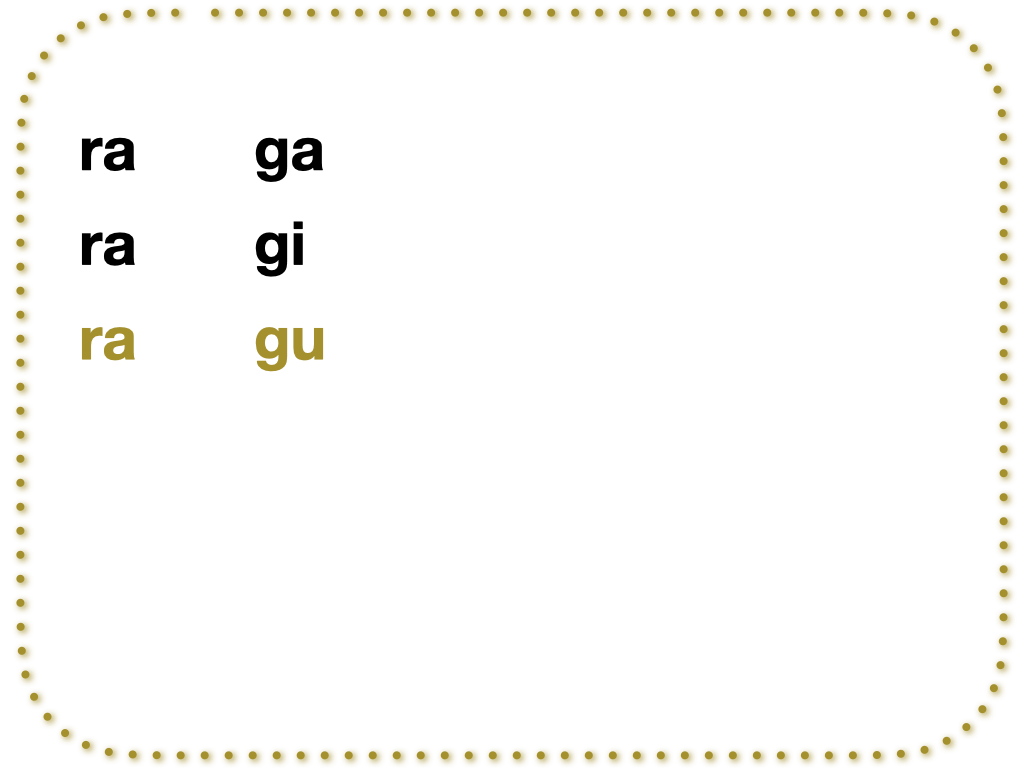

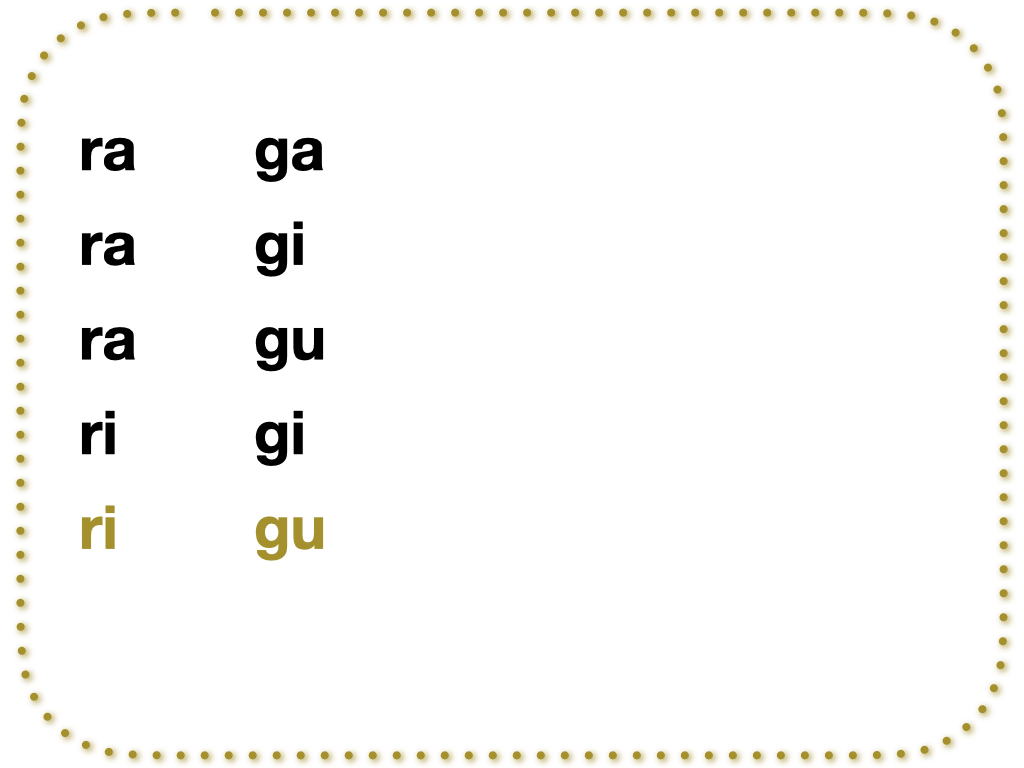

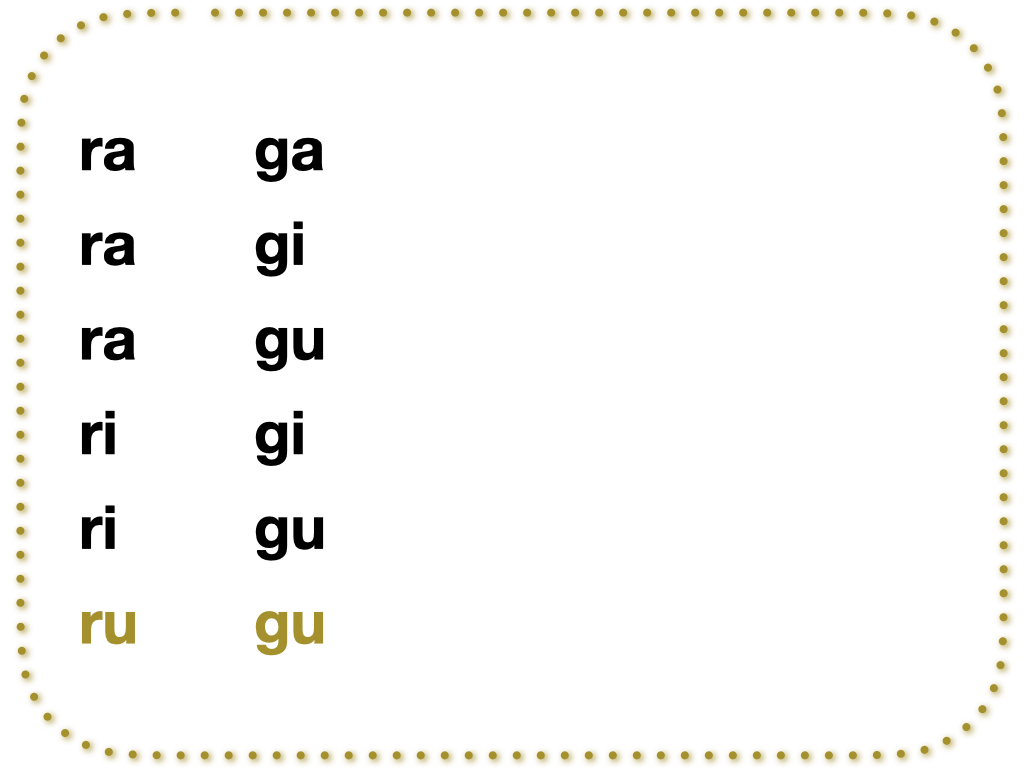

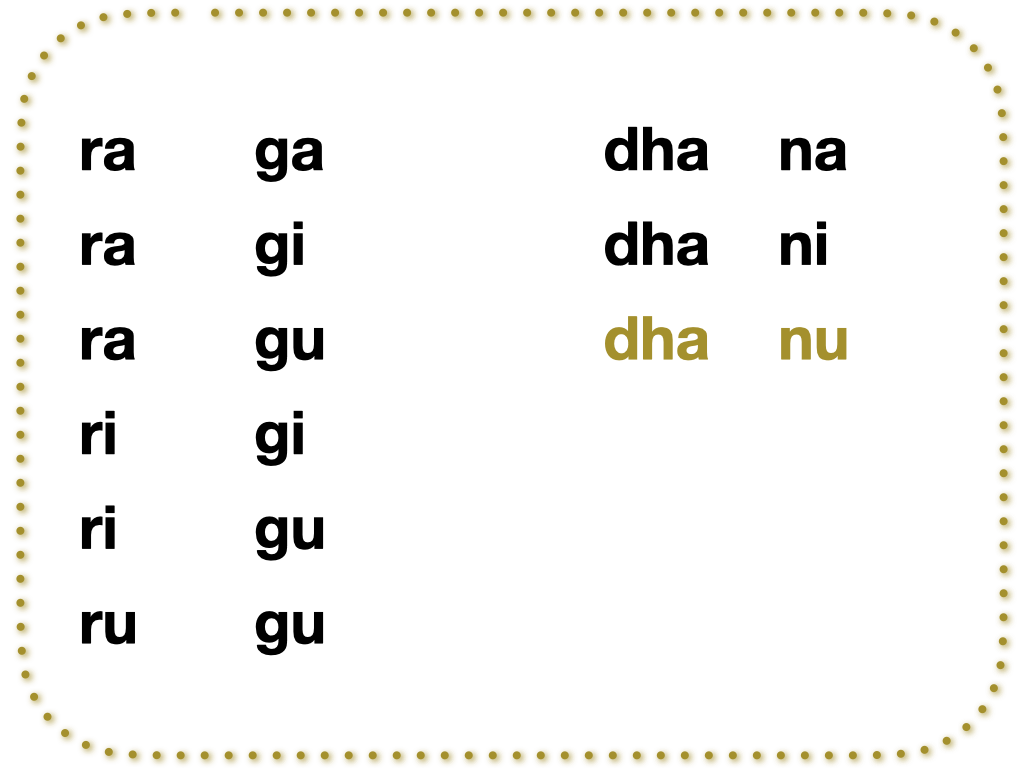

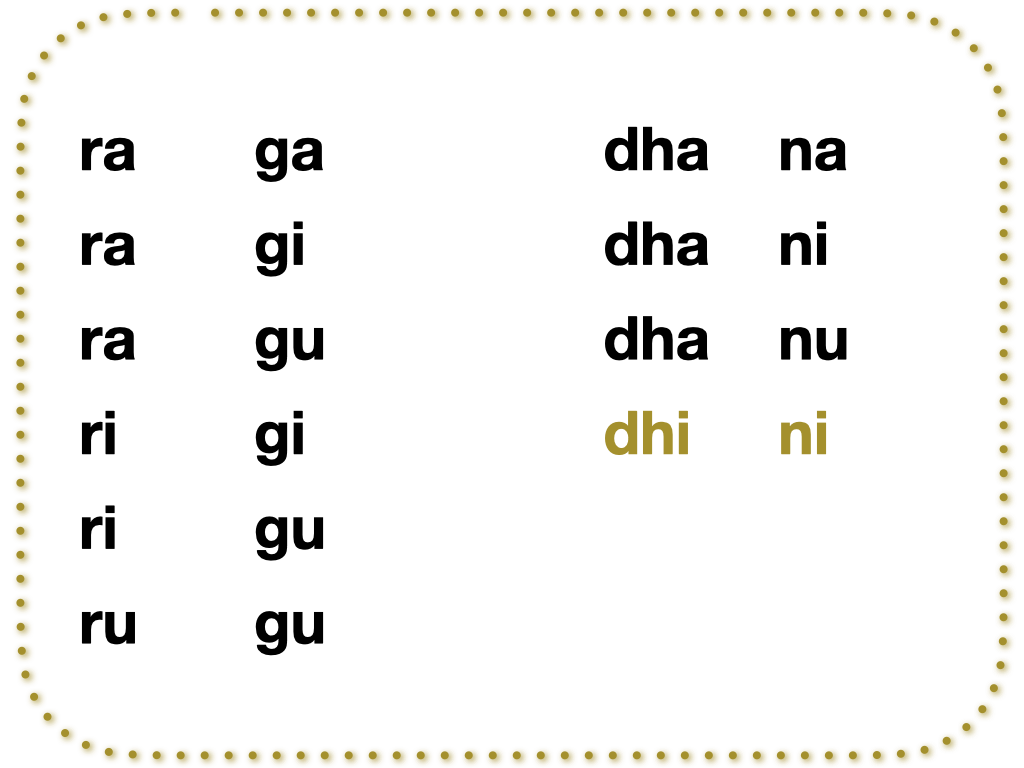

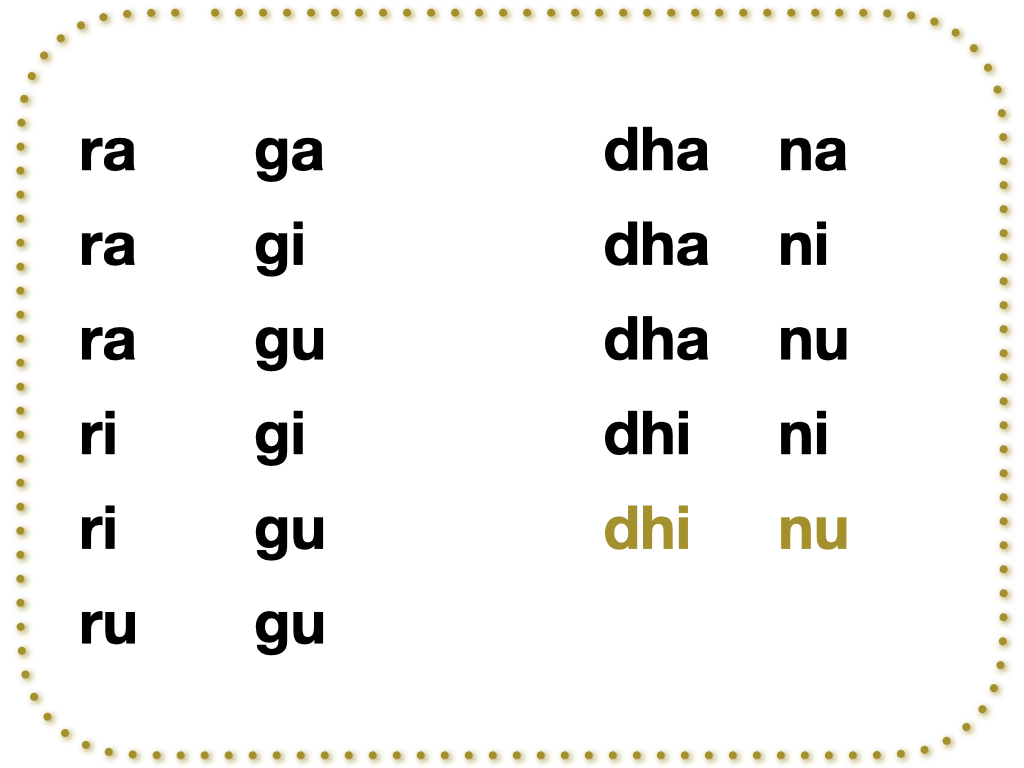

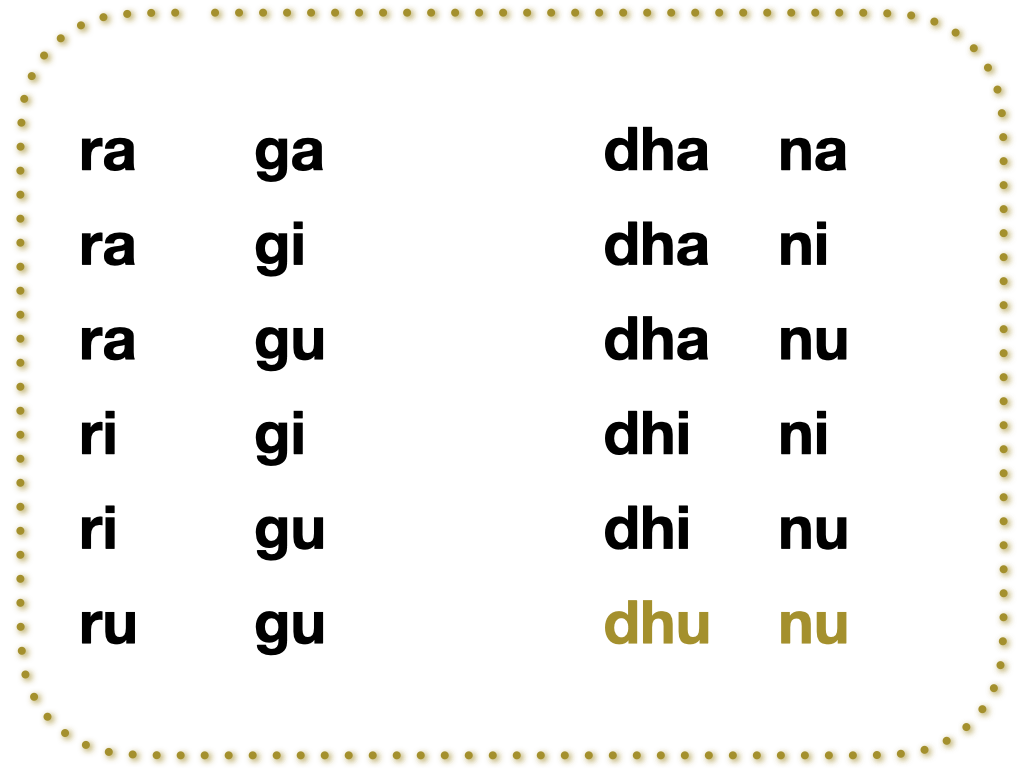

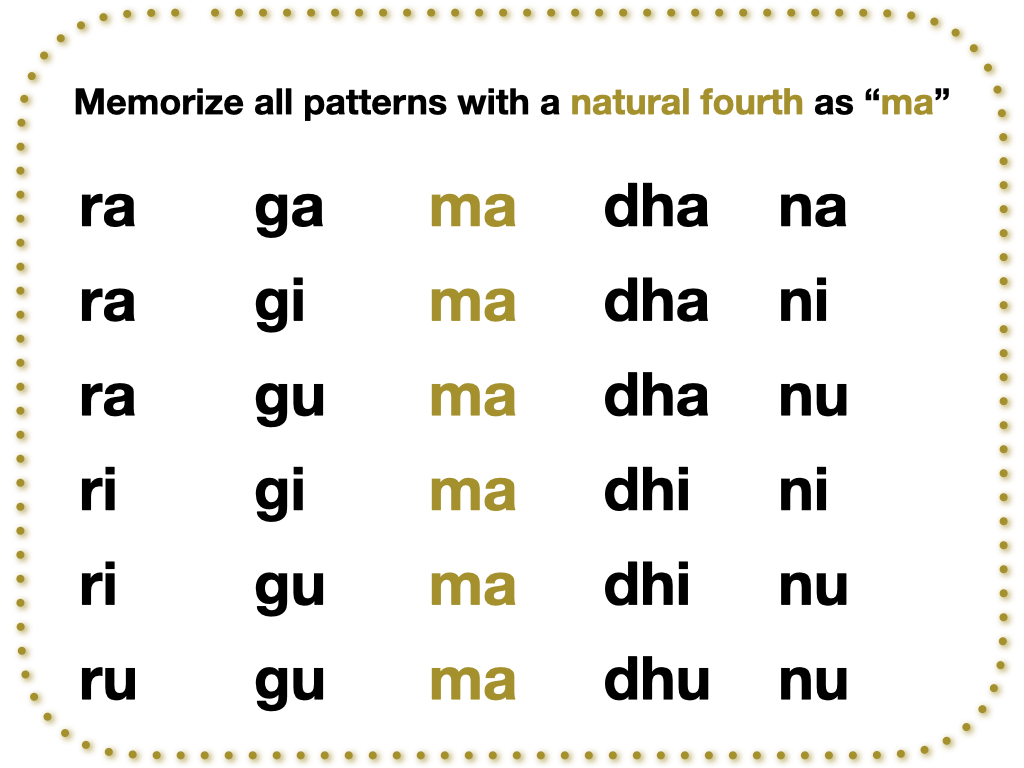

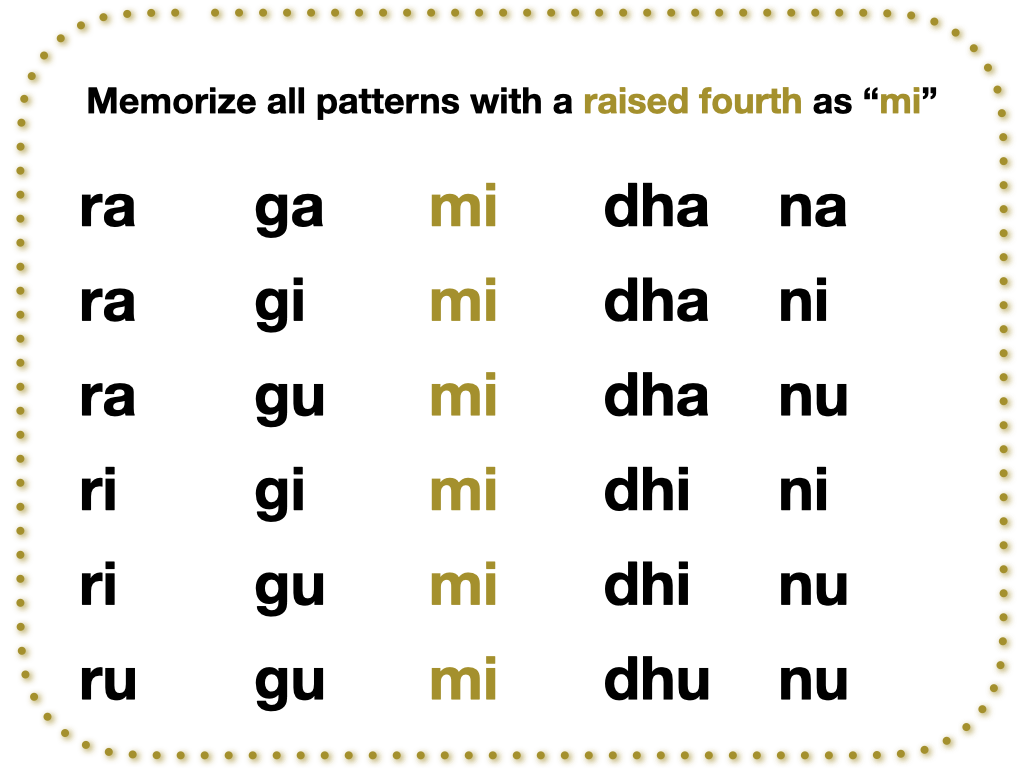

Vowel change: remember all the possible combinations of notes

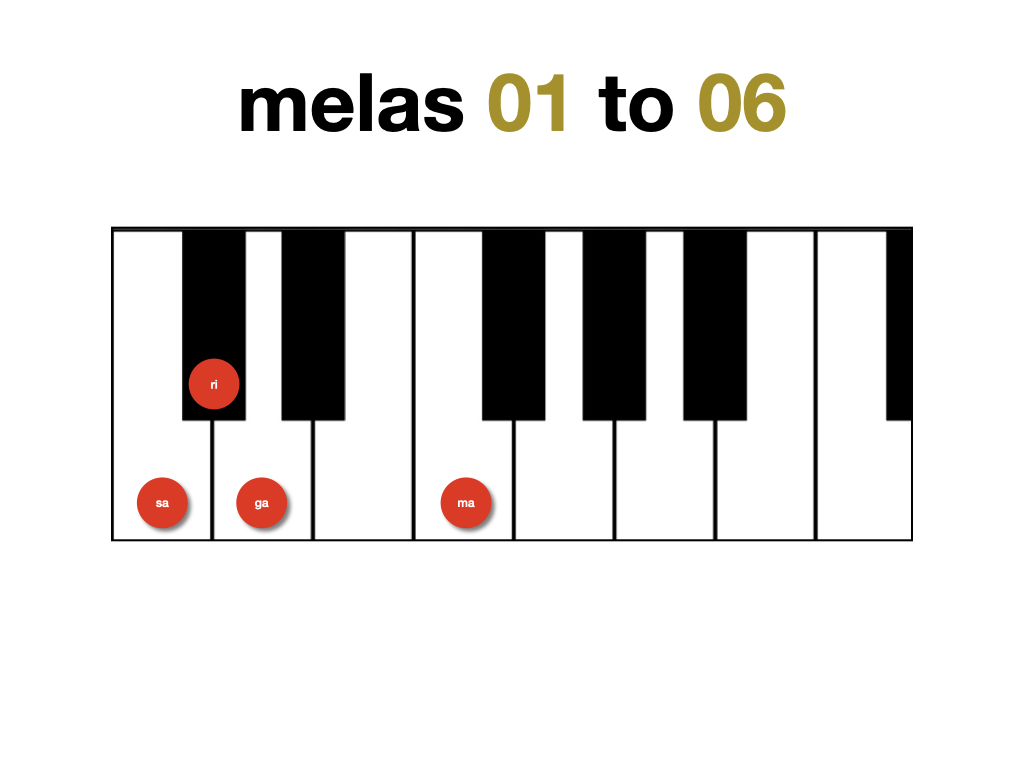

In Tanjore as a Seat of Music (p. 413), S. Seetha credits Venkatamakhi with introducing “the device of vowel change in the names of svaras”, namely “to easily remember the different combinations of the varieties of svaras” for all the 72 melas. – Explore and apply this ingenious aid to memory with the help of a slideshow and midi-sounds.

The Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music >>

How to apply this lesson (with or without personal teacher)

One of the short “Flow”-exercises offered in this course may suit your personal situation: to rekindle your joy and creativity anywhere, any time (silently or otherwise); ready to modify for group activities (even where time may be as short in supply as musical instruments and digital equipment).

How to find ragas derived from a particular mela on YouTube?

- YouTube (“melakarta raga concert”)

- Refine your search by a particular mela number:

“21“, “34” or “66“ - Search for a particular raga’s exposition: “Nathabhairavi live” (the 20th melakarta raga)

- Find performances by seasoned performers: “melakarta raga live concert 72“

Further refinement

Include a favourite musician or instrument for other results to suit your interest, for instance:

About mela ragas and their arrangement

Mēḷakartā raga is abbreviated as mela – for our purposes this merely denotes a “musical scale” (i.e. not a raga)

At a later stage, also try and remember the mēḷakartā raga names and their numbers in the manner indicated

All ragas associated with these melas are brought alive with subtle nuances (e.g. raga Kalyāṇi, derived from mela 65. and written as Mēcakalyāṇi to facilitate pronunciation)

You’ll notice that there is a relationship between the first two syllables of each mela name and the two numbers that indicate its position

The mela-number method involves a reversal of numbers, as indicated in each slide: e.g. 65. Mēcakalyāṇi M-C=56><65

For this reason, the first nine melas are numbered “01.” to “09.” (not merely “1.” to “9.”)

A few melas are shown with a tilde symbol (“~“) to highlight an exception: 66. Citrāmbari C~Tr=66><66

This exception relates to a general rule for Sanskrit mnemonics (kaṭapayādi sūtra): in our course, the combination of “~” and capitalized letter overrides the regular conjunct consonant (seen in lower-case instead)

In Sanskrit all consonants contain an “a” until modified (ka, kha etc.); this “a” is pronounced as “u” in but

The short “a” is substituted by the long “ā” or any other vowel in the names of some mēḷakartā ragas like Kīravāṇi and Kōkilapriya

A dot as in “ṭ” ट distinguishes the cerebral letter “ṭ” (e.g. Nāṭakapriya, mela 10) from its dental counterpart “t” (e.g. Latāṅgi, mela 63)

To ensure the kaṭapayādi sūtra works as intended do pronounce the “h” clearly: for instance, kha ख and gha घ are distinct aspirated consonants and pronounced as in inkhorn and log house

Three consonants corresponding to numbers 5, 6 and 7 – “ś”, “ṣ” and “s” – represent three distinct sounds (palatal ś, retroflex ṣ and dental s); these are pronounced as in she, partial and sit; in Śyāmaḷāṅgi (mēḷa 55), Ṣaṇmukhapriya (mēḷa 56) and Simhēndramadhyamam (mēḷa 57) respectively

Historical points worth pondering

This mini-course explores the infinite world of melody based on the original principles first formulated in the 17th century; and gradually evolving in musical practice in each following generation, as elucidated by by Dr. S. Seetha:

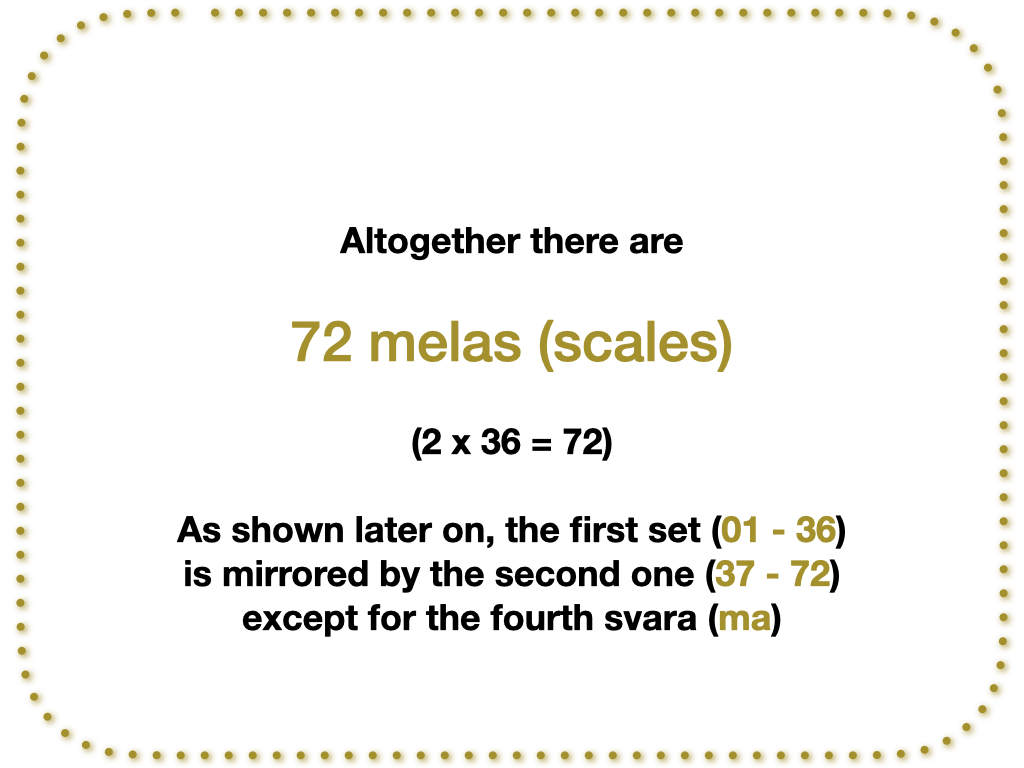

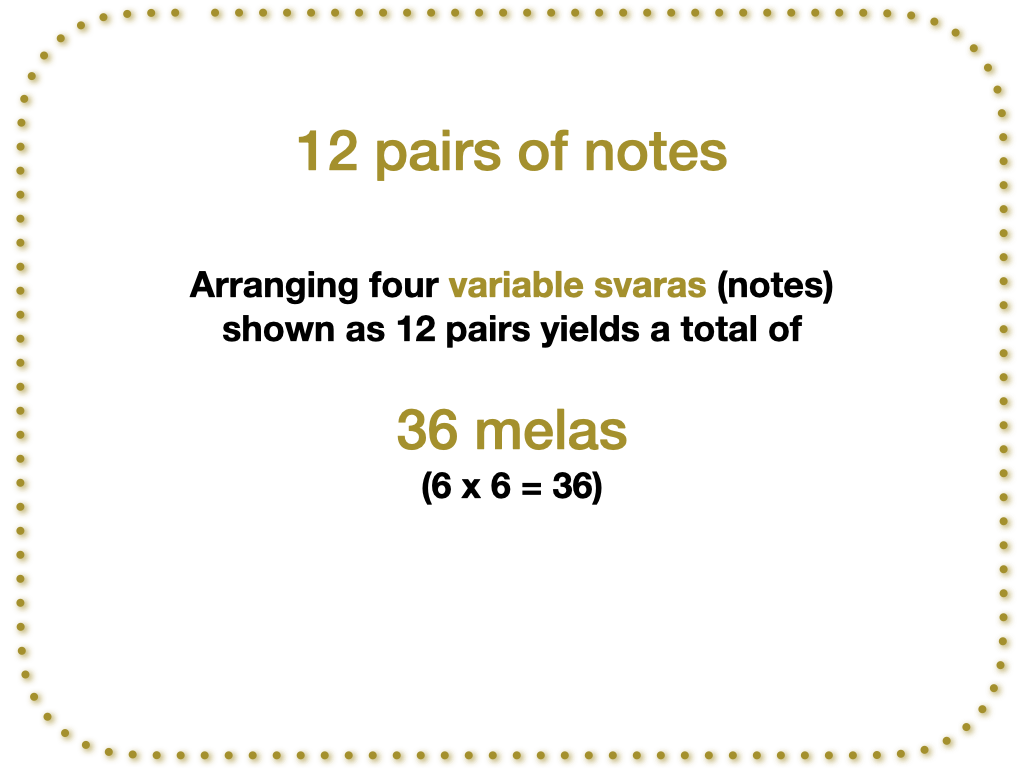

The research in the field of pure musicology yields some interesting theoretical results, useful from technical and historical points of view. Venkatamakhi while justifying the derivation of 72 melakartas by permutation and combination interestingly remarks that countries are many with people having variety of tastes and it is to please them ragas have been invented by musicians. Some are already known while some are in the process of being brought to life, while some may be invented in future, while those surviving only in treatises and the ragas not known at all during their time may be brought to life in future, for the benefit of the people.

Tanjore as a Seat of Music (During the 17th, 18th and the 19th Centuries) by Dr. S. Seetha (University of Madras 1981), pp. 433-4 [Download Link]

Will listening habits prevent scientific and artistic advances?

Probably not, going by neuroscientist Dale Purves: his research gives fascinating insights into preferences shared by members of different cultures since antiquity.

He distinguishes the scope for countless scales yielded by combining all the available semitone and whole-tone intervals of a modern keyboard; and discusses those combinations that are preferred all over the world, be it among Indian, Chinese, Arabic and Persian musicians and listeners or among their Western counterparts (in jazz, blues, popular or “folk” music, early liturgical just as “classical” music):

The rationale is based on the summed similarity of the intervals in the scale to a harmonic series. The greater the similarity, the greater the appeal based on the biological value of recognizing and responding to this salient characteristic of human vocalization.”

He also points out that innovations initially rejected by listeners may become “standard classical fare” later. For this he cites the ballet music for “The Rite of Spring” by Igor Stravinsky (marked by a wide range of chromatic tonalities as well as unconventional rhythms and meters).

A similar conclusion may be drawn given the time that passed since Venkatamaki’s described his pathbreaking innovation (in a period marked by intercultural relations) and its exploration since the early 20th century (among Carnatic as well as Hindustani music scholars, performers and composers).

Source: Music as Biology: The Tones We like and Why by Dale Purves (Harvard University Press 2017), pp. 66, 69 & p. 73

Summary: Why do human beings find some tone combinations consonant and others dissonant? Why do we make music using only a small number of scales out the billions that are possible? Dale Purves shows that rethinking music theory in biological terms offers a new approach to centuries-long debates about the organization and impact of music.

What about the modern mela-nomenclature (the Kanakāngi-Ratnāngi scheme)?

In Tanjore as a Seat of Music (p. 420-426), S. Seetha explains some of the changes that took place since Venkatamakhi proposed his original mela arrangement: “varali ma” became known as “prati ma” since the late 18th c. when a scholar known as Govindacarya wrote his treatise, the Sangrahacūdamani.

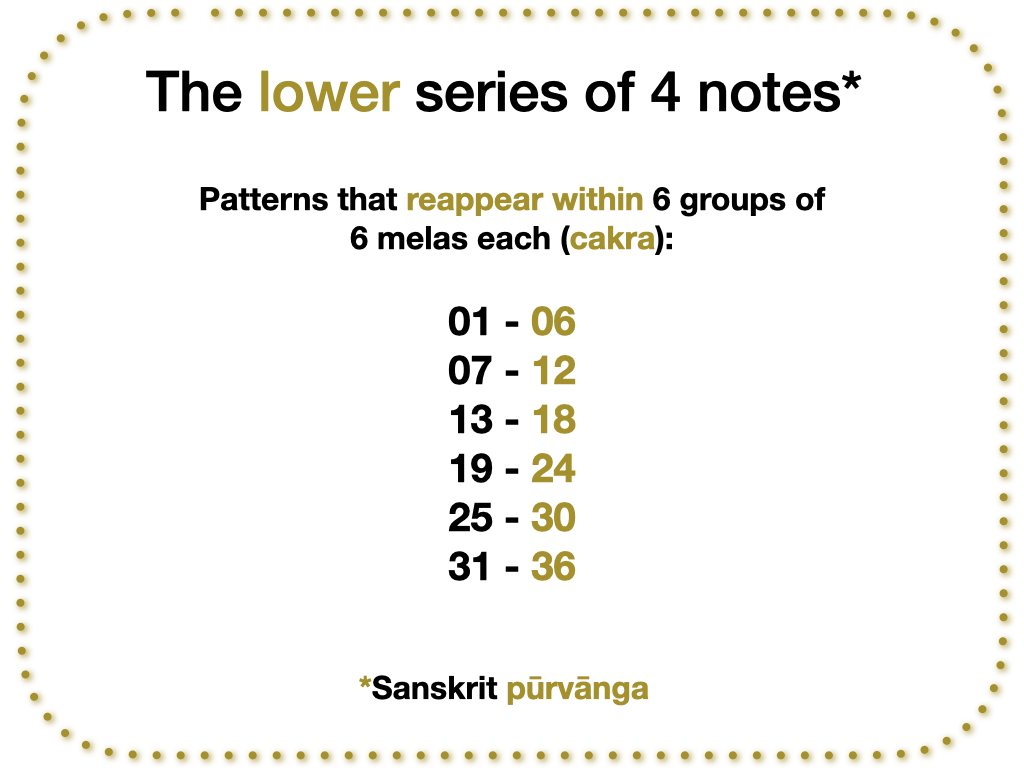

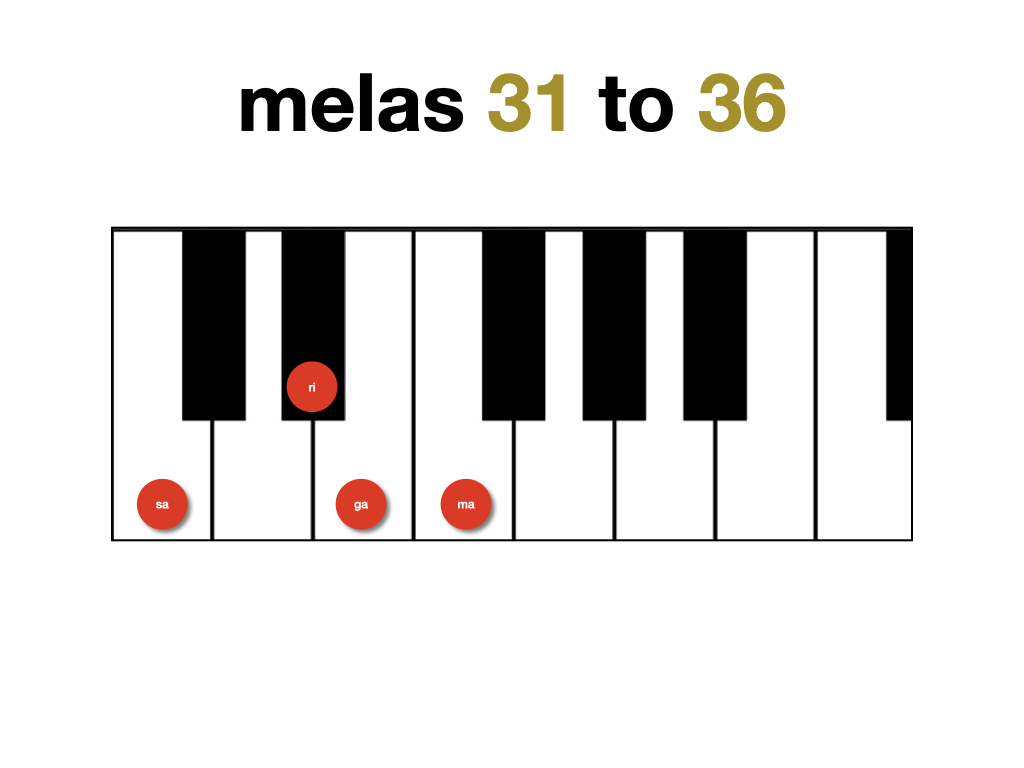

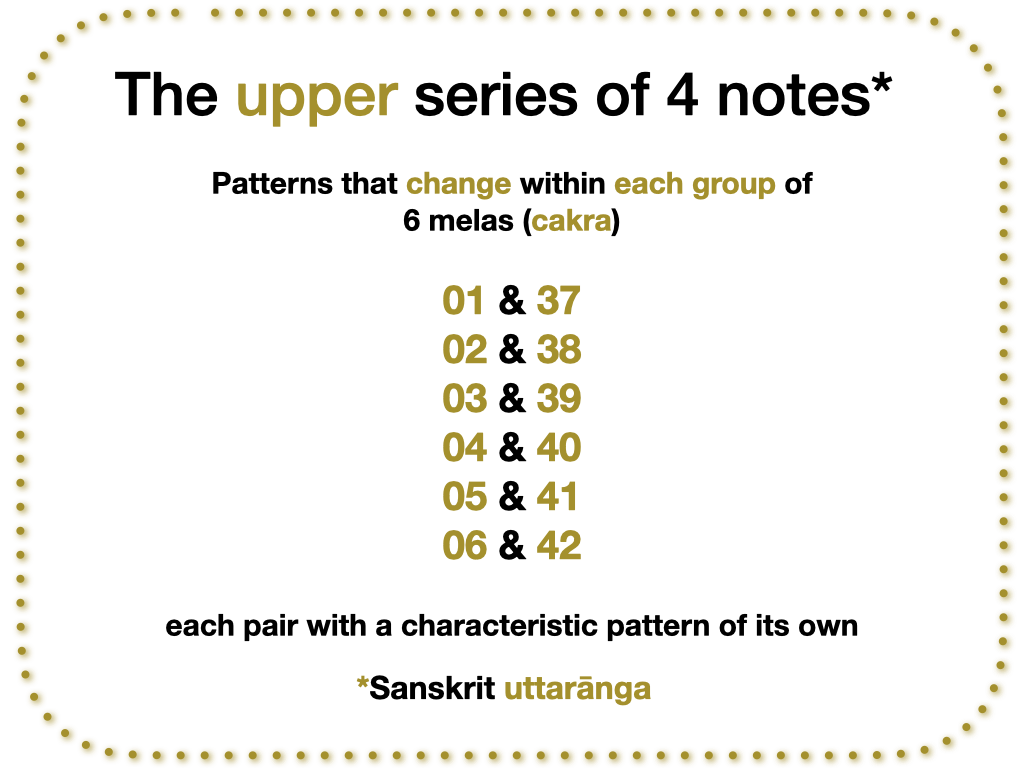

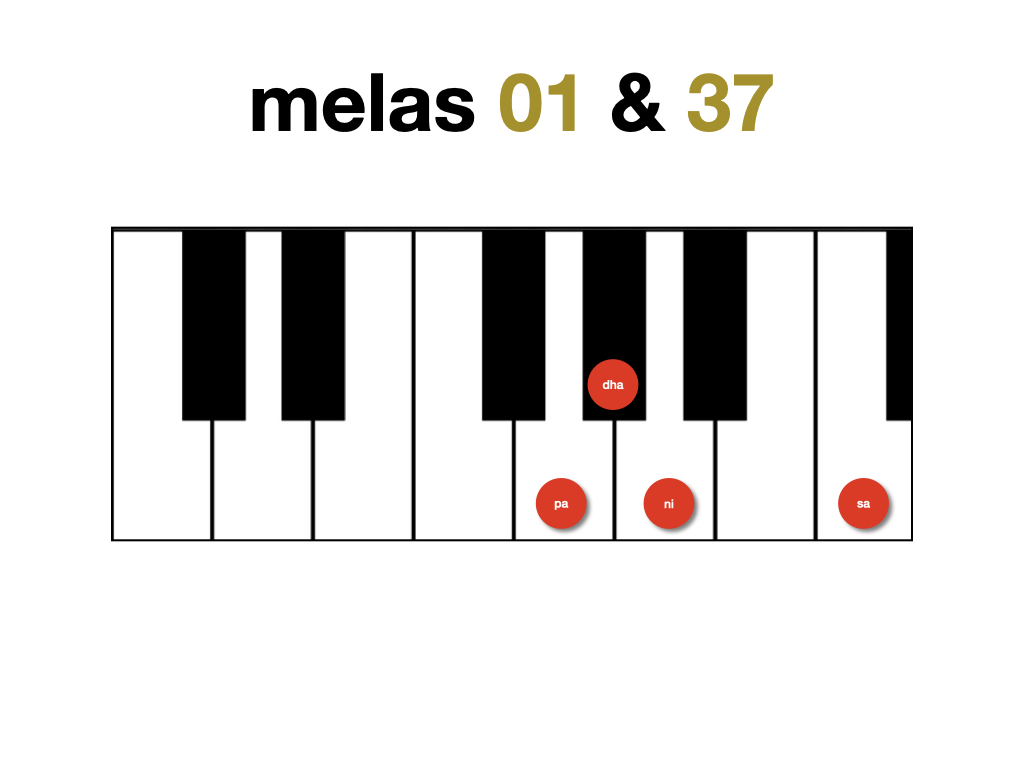

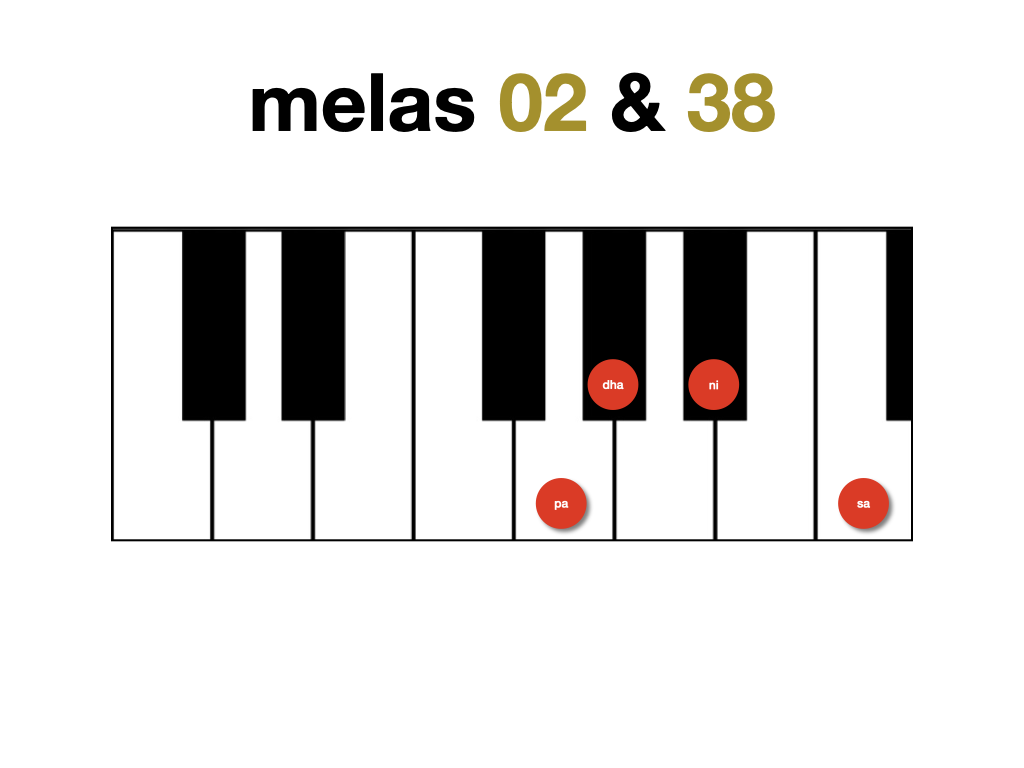

Govindacarya also had good reasons for giving the 72 melas individual names within the famous list, the Kanakāngi-Ratnāngi nomenclature: it helps musicians and listeners “ascertaining the mela and the kinds of notes taken both in the purvānga [Sa-Ri-Ga-Ma] and uttarānga [Pa-Dha-Ni-’Sa]”.

As a result, “the melakarta assumes a real scientific meaning during Govindacarya’s time […] and help in the preservation of the identify of many a janya [derived raga]. […] The ragas assume different colours and shades of expression in their attempt to satisfy the musical needs and tastes of the people. But the 72 melakartas are perhaps ever the same in structure and remain as the material forever out of which the thing of beauty – the raga – is made. […] Whether the janya is the one derived from the melakarta or vice versa, the existing janaka-janya system of raga classification enhances the paramount importance of the 72 melas as technical facts defining the janyas under them”.

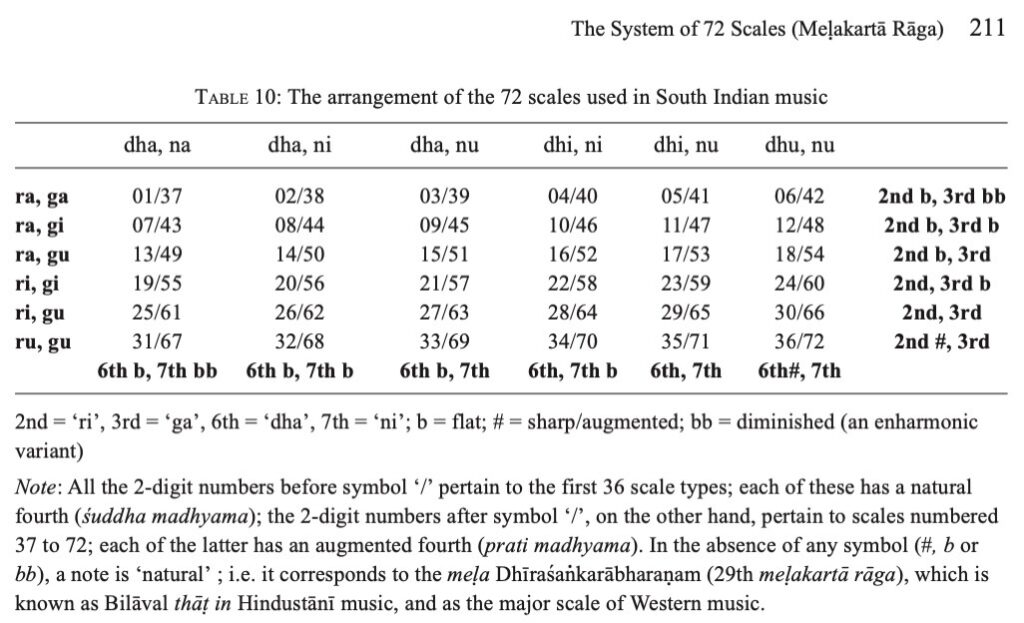

And what about Hindustani scales (that) and those of Western music?

All the ten scales of Hindustani music (that) are found among the 72 melas. And the same applies to the scales and modes of Western music.

For details, refer to the print-friendly PDF attachment >>

“The similarity between Indian and old European music has struck every investigator, and can be traced theoretically as well – an interesting field for research, and one hardly explored yet.” – Musicologist Arnold Bake in a lecture delivered at the India Society London in 1930; for details see Unity in Diversity, Antiquity in Contemporary Practice? South Indian Music Reconsidered (footnote 74) >>

Tradition and change: integrity matters, even in the digital age!

In this course, new exercises are introduced with due respect for integrity – respect for a music that has evolved over several centuries (in its present concert format) and far beyond (as regards thought provoking concepts that kindle long-term immersion).

Some of the exercises and methods facilitate continuous or frequent practice among learners who struggle with multiple commitments.

So this is all about the kind of active involvement in a tradition wherein music is simply indispensable for leading a fulfilled life. This also explains why long-term commitment is compatible with socio-economic and scientific change. This calls for imagination, a fact reflected in text books that highlight the importance of manodharma sangita, a concept reaching beyond “improvisation” as understood in Western music.

We may therefore safely conclude that both commitments, learning and teaching, are by no means determined by an individual’s station in life.

For this reason, lessons may either be shared regularly and personally (by a guru, in the past largely informally within a household known as gurukulam), or without personal contact by emulating an inspiring exponent – alive or otherwise (manasa guru, manasika guru). Many musical biographers and hagiographers share a conviction that a learner’s choice for either approach – personal or indirect lessons – tells little if anything about an accomplished musician’s status.

In short, this is all about dedication and integrity, even in the digital age!

Find out more | Follow another (free) mini course which includes a special gift for all motivated learners >>

Enjoy your learning experience!

Ludwig Pesch

PS To bring errors to my attention and for comments, feel free to contact me >>

Related post: Flow | Exercises, related resources & tips >>